Issue 66: the women printers, publishers, and content distributors who came before me

'Despite their under-representation in the records and the patriarchal nature of society in this period, women were an active, and often prolific, part of the printing trade in early modern London.'

When I first read about a particular broadside published by Elianor James1 circa 1715, I envisioned this post as a reflection on whether her statements of 300+ years ago still rang true today.

James was a writer, printer, and political activist in late 17th and early 18th Century London. She defied expectations for women at a time when they were legally and socially constrained. Indeed, contemporary commentator John Dunton wrote in 1705 in his ‘Life and Errors’ that Thomas James, also a printer, was “better known for being husband to that she-state-politician Mrs Elianor James”.

In the early 18th Century, with “above forty years” experience under her belt, she wrote and printed ‘Mrs James's Advice to all Printers in General’.

I imagined that perhaps she might have advocated for tidiness in the print workshop, accuracy in the setting of type, care in the handling of still-wet pages, etc.

My ideal scenario was that her advice would include principles that are relevant to my own writing/publishing practice, and I would be able to consider the similarities and differences between James and myself across the centuries.

But that imagined post was not to be.

It turns out James’s advice was a plea against encouraging the absconding of apprentices before they’d served their full term (usually seven years), against giving them work it they did abscond, or paying them for that work. She said any of the above would be “to the ruin of the trade in general, and the spoiling of youth”.

No original copies of the broadside are thought to survive, but in 1821 John Nichols reprinted it in full in the first volume of his ‘Literary Anecdotes of the Eighteenth Century’. It shows us how James wished to:

“have this great evil prevented, and that you may easily do, if you will resolve to take no man's servant from him […] if it should happen, that an apprentice by any trick should get away from his master, I would not have you give any encouragements, as money, but that he should serve the term of his indenture. […] pray, brother, do not be guilty in destroying the youth, for it is the destruction of the trade.”

Despite my original story idea being relegated to the metaphorical printing room floor, Elianor James – and the role of women in printing in the early modern period more broadly – is still worthy of our attention.

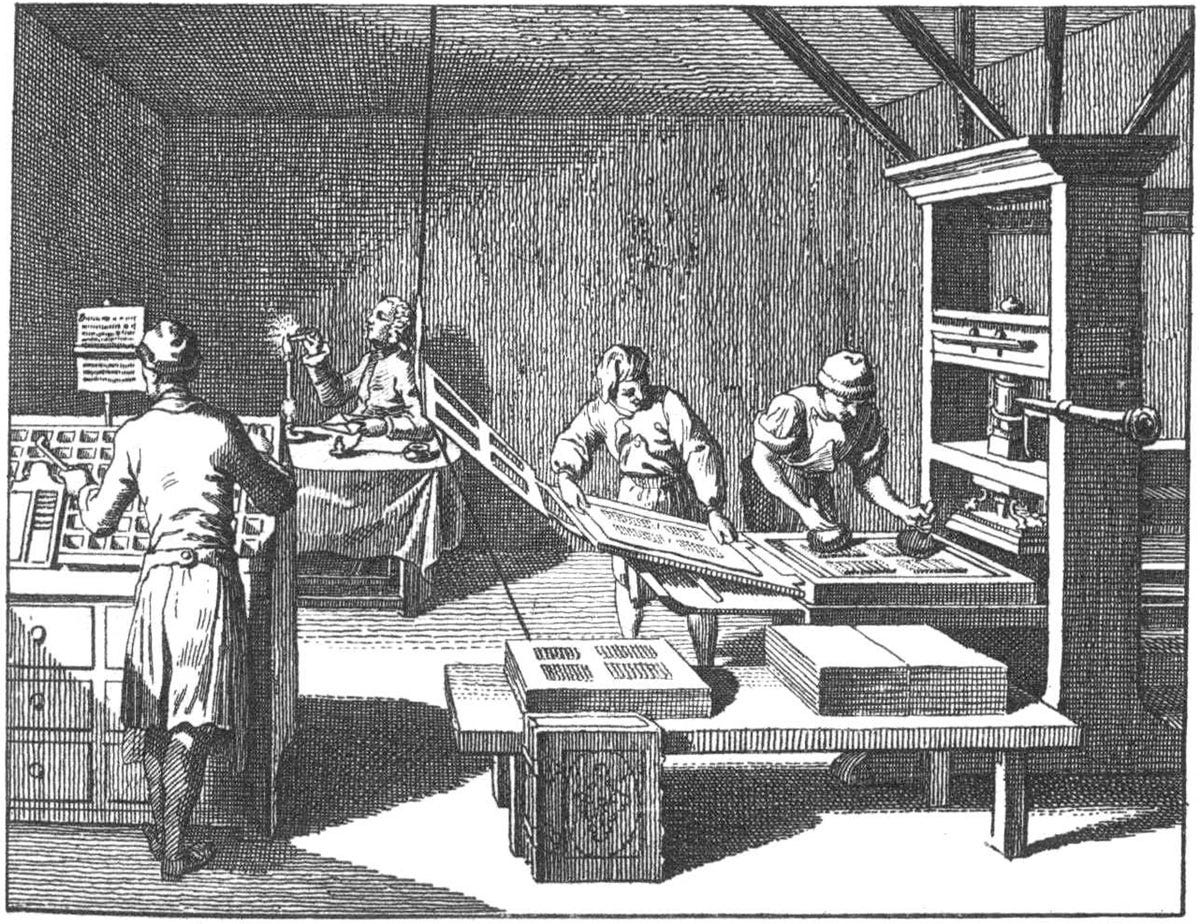

The first mechanical movable type books were printed in England in 1477. But as early as 1403, the craftspeople that made up the book trade in the City of London had been given permission to form a guild: the Stationers’ Company. It was granted a royal charter in 1557 and survives to this day as the livery company for the communications and content industries.

The guild was home to printers, type founders, parchminers (providers of parchment), limners (illustrators/illuminators), book binders, and book sellers, who contributed to the production and distribution of everything from books and newspapers to pamphlets and broadsides, and even the indenture forms on which apprentices were recorded across the suite of London livery companies.

Livery companies were at the heart of all the trades in the City of London in the early modern period. And those trades were powered in significant part by apprentices, who were predominantly male, bound to masters, who were predominantly male. An analysis of Stationers’ Company records between 1500 and 1750 reveals details for 29,270 apprentices and freemen (‘freeman’ was the requisite status for becoming the master of an apprentice). Of these, just 435 (1%) are women (after removing duplicates, the number of unique women is just 255).

But – as is often the case when researching women from history – the official records don’t tell the full story.

C. J. Mitchell argues that “most female labour goes unnoticed in the kind of records that have survived” and, given that businesses into which apprentices were taken were family based, wives and daughters would have been an integral part of operations. “By this measure, therefore, females constituted some half of the book trades workforce.”

So, despite their under-representation in the records, and despite the patriarchal nature of society during this period, women were an active, and often prolific, part of the printing and publishing industry in early modern London. Historians including Maureen Bell, Lisa Maruca, and Helen Smith have cited examples including:

printer Hannah Allen, who bound at least 12 apprentices between 1691 and 1724

printer Elizabeth Purslow(e), who was responsible for at least 164 works in the early-to-mid 17th Century

the Griffin family print business, active in the 17th Century, which was owned and run for around 50 of its 66-year history by two women

Mary Cooper, an early 1740s trade publisher (a type of middleperson between the copyright owner and the buying public), who is named in two-thirds of all known imprints in the period, sometimes more than 100 per year

Tace Sowle, a prolific (over 200 imprints) and multi-talented stationer – described by John Dunton as “both a printer as well as a bookseller [... and a] good compositor” – active in the late 17th and early 18th centuries

plus, evidence of at least 20 women who, after their husband’s deaths, carried on the family business for 10, 20, or even more years

Elianor James (1644/5-1719) was another of those prolific women.

She married the printer Thomas James in 1662, and when he acquired his own press in 1675, she took advantage of its proximity in their home to express her opinions to the masses.

Between 1681 and 1716, she wrote, printed, and distributed more than 90 pamphlets and broadsides on political, religious, and commercial topics. She called them names such as ‘Mrs James’s Advice…’, or ‘Mrs James’s Vindication…’, and advertised her authorship in large letters at the top of the texts.

Some of the works document speeches she gave at Guildhall (home of London mayoral activities) and Westminster (home of national government activities), and others were variously addressed to authorities including the reigning monarch, the houses of Lords and Commons, and the Lord Mayor of the City of London.

Making her outputs even more intriguing is the suggestion from Paula McDowell in her biography of James that she “may never have ‘written’ her broadsides at all, but rather composed them directly at the printing press with type”.

When her husband died in 1710, James carried on managing their printing business and chose to donate his (their?!) personal library of around 3,000 books to the Church of England clergy’s Sion College, along with portraits of her husband and herself.

James was middle-class, yes, but she was also a tradeswoman. And today her portrait – which it's believed she commissioned, and features one of her most famous works, ‘Mrs James’s Vindication of the Church of England’, published in 1687 – hangs in the National Portrait Gallery, a testament to her influence and historical importance.