Issue 29: how the world’s most famous vampire ended up in Essex

The evidence of the real-life inspiration for Dracula’s English home, Carfax.

Since early May I’ve been reading Bram Stoker’s ‘Dracula’ via email, in real time as it happens in the book. That is to say, the clever folks at

created , a newsletter that shares the novel in small, digestible chunks, on the days the letters, diary entries, telegrams, and newspaper clippings it comprises are dated.I’ve gotta say – it’s a great newsletter concept. As someone who now largely works from home and doesn’t have that regular commuting time to read a book, I’ve enjoyed being able to get through a novel as part of my daily inbox management. I’ll miss it when the story concludes next week.

This is the first time I’ve actually read ‘Dracula’. I’ve seen the films and television mini-series based on it. I was even involved in editing a script of it for an ill-fated ‘transmedia’ project in the 2010s. But reading it each morning over my muesli, I learned for the first time that Count Dracula’s Carfax estate – and a lot of the book’s action – is based in Purfleet, Essex.

Five years ago, this probably wouldn’t have meant much to me. But in 2017 I moved further to the east of London, from where Purfleet is just a few miles down the road.

So, I was intrigued to find out if Stoker had based the fictional vampire’s English home on real life landmarks near my own home.

In chapter two, in a diary entry dated 5 May, Jonathan Harker describes the estate he’s acquired on the Count’s behalf:

“At Purfleet, on a byroad, I came across just such a place as seemed to be required, and where was displayed a dilapidated notice that the place was for sale. It was surrounded by a high wall, of ancient structure, built of heavy stones, and has not been repaired for a large number of years. The closed gates are of heavy old oak and iron, all eaten with rust.

“The estate is called Carfax, no doubt a corruption of the old Quatre Face, as the house is four sided, agreeing with the cardinal points of the compass. It contains in all some twenty acres, quite surrounded by the solid stone wall above mentioned. There are many trees on it, which make it in places gloomy, and there is a deep, dark-looking pond or small lake, evidently fed by some springs, as the water is clear and flows away in a fair-sized stream. The house is very large and of all periods back, I should say, to mediaeval times, for one part is of stone immensely thick, with only a few windows high up and heavily barred with iron. It looks like part of a keep, and is close to an old chapel or church… The house had been added to, but in a very straggling way, and I can only guess at the amount of ground it covers, which must be very great. There are but few houses close at hand, one being a very large house only recently added to and formed into a private lunatic asylum. It is not, however, visible from the grounds."

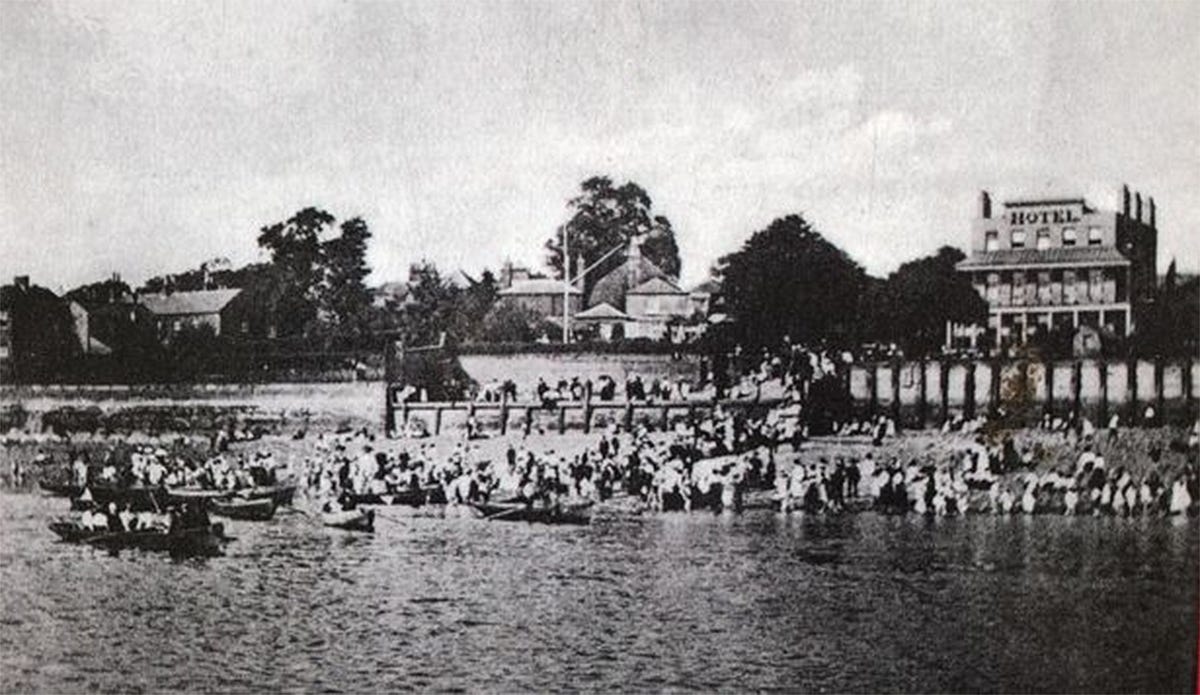

‘Dracula’ was published in 1897. From 1878-1904 Stoker was manager of London’s Lyceum Theatre. Around the same time, Purfleet – then a rural riverside leisure attraction – was a popular location for day trips out of London (a regular pastime of the theatrical set when theatres were closed on Sundays). The waterfront Wingrove’s Hotel – which survives to this day as the Royal Hotel – offered bathing facilities and a famous whitebait supper.

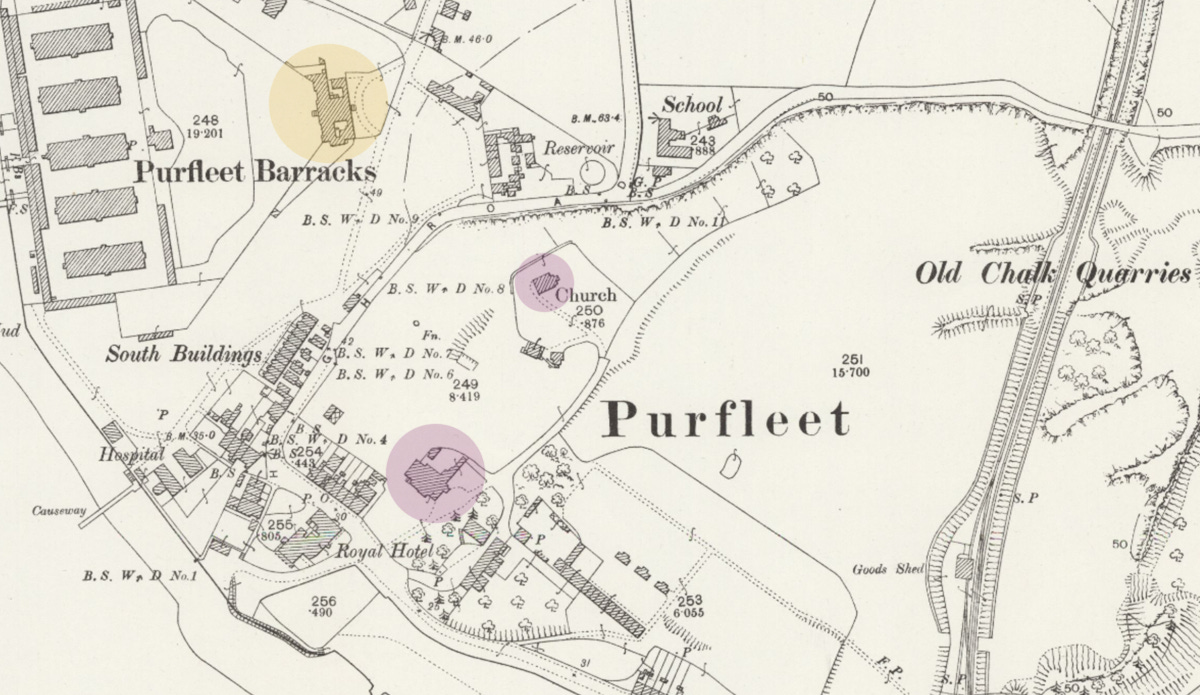

Across London Road, behind the hotel, was Purfleet House, built in 1791 by Samuel Whitbread, founder of the Whitbread & Co brewery and a member of parliament. Local historians agree that Whitbread’s estate (demolished in part in the 1920s and completely in the 1950s) was the inspiration for Carfax.1

Details from the sales catalogue when Purfleet House was auctioned in the 1920s describe is as having 20 bedrooms, a dining room, drawing room, large paved kitchen, and adjoining store. It was set over three floors and also boasted large cellars.

The estate was set in an old chalk quarry and included a range of outbuildings. As quarrying tends to go below the waterline, this could be the source of the pond mentioned in the book. The five acres of grounds also featured a pleasure garden which was open to the public, including those aforementioned London day-trippers.

Among the outbuildings was a small church located towards the back of the estate, which remains standing, albeit totally derelict.

Today, St Stephen’s Church is located where Purfleet House once stood. Historians say stone from the Whitbread’s home’s partial demolition in the 1920s was used in the construction of the church.

Some sources I’ve consulted say that a brick and flint wall still standing today on Tank Hill Road – what would have been the lower west side of the Whitbread estate – corresponds with the one described by Jonathan Harker, above. Another contender are the large inner and outer walls which protected the nearby Royal Gunpowder Magazines in Purfleet Barracks.

And the neighbouring asylum in Stoker’s novel? The historians’ consensus is that it was based on Ordnance House, the residence of the gunpowder storekeeper.

Incidentally, the only remaining magazine of the original five (which each stored around 10,000 barrels of gunpowder for the army and navy and were in use for over 200 years from the mid-1700s to mid-1900s) today houses the Purfleet Heritage and Military Centre. The volunteer-run centre features a small exhibit about Dracula’s link to the area.