Issue 69: Marianne North didn’t do what was expected of her

She was a single, solo traveller whose art straddled styles, and who took matters into her own hands to secure her legacy.

Marianne North (1830-1890) was a woman who knew what she wanted and had the means and motivation to make it happen. From travelling the world to see firsthand the exotic plants that fascinated her, to designing and financing a gallery to save her art for posterity and the “pleasure of others”.

As Dr Lynne Howarth-Gladston sets out in her book, ‘Marianne North: A Victorian Painter for the 21st Century’, North was an unconventional botanical artist as well as a progressive and multi-faceted individual. Her life and work continue to resonate with contemporary themes, not just of art and science, but of feminism and environmentalism, too.

She’d developed an interest in exotic plants in her mid-20s after a visit to the Palm House at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew in 1856. She said it made her “long to see the tropics”.

North never married. She considered it “a terrible experiment” that turned women into “a sort of upper servant”. She wasn’t interested in a man controlling her or the finances she was set to inherit.

So, when her father, Frederick North, a member of the British parliament, died in 1869, the last tie binding her to home was gone and she was free to pursue her ambitions.

In 1871, aged 40, she set off on her travels – on her own – arriving in Jamaica in December. Yes, she had letters of introduction to help facilitate her passage, but she travelled without an entourage, porters, or a maid (as was typical at the time). She packed light so she could carry everything herself. And once she reached her destinations, she avoided the leisure activities of the colonial British expats. Instead, she consulted with locals and headed for the hills and forests to find the exotic plants she’d come to paint; “the flowers in their homes”, as she put it.

Over 14 years she visited 16 countries across five continents.

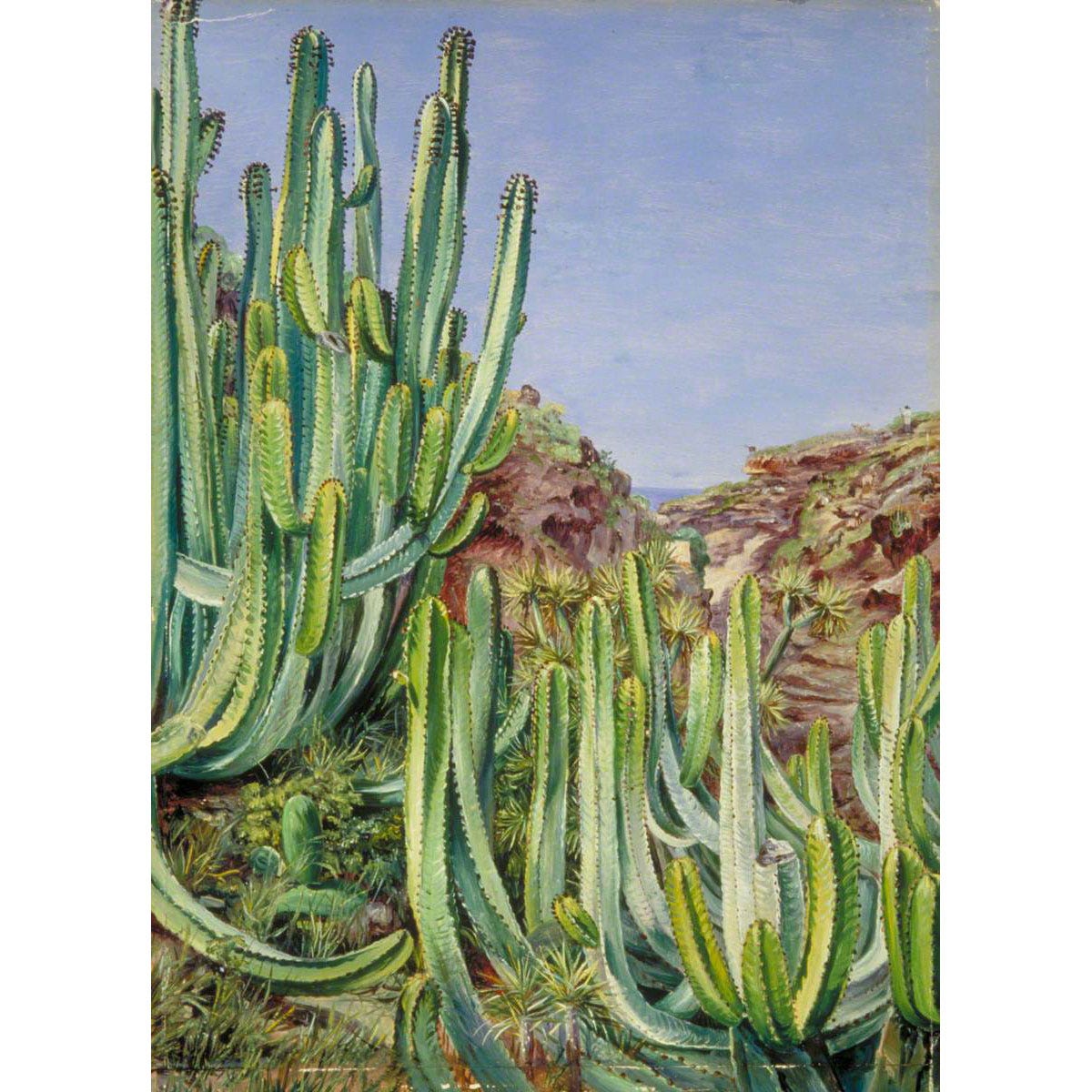

North’s artistic style wasn’t quite the ‘Victorian lady flower painting’ considered proper for women in this period, nor did it adhere to the specialist conventions of botanical illustration. But what North did which others did not, was to often paint both close-ups of individual plants as well as wider landscape views showing them in their natural habitats, sometimes including animals, insects, and humans.

Her artistic approach may not have been conventional, but it proved valuable for multiple audiences. In a time before colour photography, North’s intricate and vibrant paintings provided a realistic glimpse of exotic flora and fauna many people were unlikely to ever see in real life. And the quality and accuracy of her depictions helped botanists identify species previously unknown to Western science.

When I visited Kew Gardens recently, I was told how the director at the time, Joseph Hooker, sent collectors out to gather specimens of certain plants having learned of their existence from North’s paintings.

In her lifetime, several newly-described species – first identified from her artworks – were named in North’s honour, including the Bornean pitcher plant, Nepenthes northiana, and the Bornean crinum, Crinum northianum.

As recently as 2021, a botanist at Kew used one of her paintings to confirm the identity of a specimen collected a century later in 1973. The blue-berried plant from Borneo has been named Chassalia northiana.

Through her work (and it must be noted, her wealth and social status, too), North built connections with leading artists and scientists, including Charles Darwin (of ‘evolution by natural selection’ fame). He is said to have told her: ‘you haven't painted all the plants of the world until you’ve been to Australia’. And so, she went there in 1880.

It is interesting to note in her diaries – published after her death in three volumes between 1892 and 1893 – North’s frustration with the introduction of non-native species by colonists. She recounts being taken to admire a plant and immediately recognising it as being from the UK, rather than indigenous. She also comments on the negative impact of capitalism on the natural environment during the 19th Century, both at home and abroad.

It was in between trips to India and Australia, in 1879, that North approached Hooker and offered her paintings to the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. She said she wanted to “leave something behind which will add to the pleasure of others”.

She would build a gallery to house the art at her own expense. This gave her complete control over exactly what it would look like, and exactly what paintings would be hung and in what order. She also wrote the guide to the gallery, drawing on notes from her extensive travel diaries. It opened to the public in 1882.

The Marianne North Gallery contains 848 paintings – oil on paper mounted on board – hung densely together, grouped in sections for the various parts of the world North visited. She intentionally mounted them in a jigsaw-like manner to prevent anyone trying to rearrange them against her wishes. Her contemporary, the poet and author Wilfrid Blunt, described the hang as like stamps in "a gigantic botanical postage-stamp album".

A volunteer at the gallery told me that the space is not only unique to Kew, but that “there’s nothing like it in any other botanic garden” either.

As Howarth-Gladstone writes in her book: "Marianne North was a significant contributor to 19th Century science and culture, not only as a botanical painter but also a global traveller, plant finder, and diarist. [...]

"North's agency as a financially independent woman in a still intensely patriarchal Victorian society [was progressive. … She] did not identify as a feminist, but is in many ways a role model for women's independence."