Issue 64: the long-overlooked women who helped return Nazi-looted art

‘Like many other histories from World War II, that of the Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives section aligned with the male-dominated narrative of events for many decades’.

If all you know about the World War II-era Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives section comes from the 2014 George Clooney-led film, ‘The Monuments Men’, you wouldn’t be alone. But what the film only briefly touches on in its final few minutes is the story that came after the war-time action.

The post-war story is one that continues today, over 80 years after the original US Government commission to protect and salvage artistic and historic monuments across Europe. And it’s a story in which the important contributions of women – including six from Britain – have long been overlooked.

Indeed, it was only two years ago that the US-based foundation which honours the legacy, and continues the work, of the Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives section (MFAA) changed its name from the Monuments Men Foundation for the Preservation of Art to the Monuments Men and Women Foundation.

“Like many other histories from World War II, that of the MFAA aligned with the male-dominated narrative of these events for many decades,” a spokesperson for the Foundation told me this week.

“To counter this male-dominated narrative of history, we decided to change the Foundation’s name to include women and acknowledge all of the individuals responsible for saving priceless works of art both during and after World War II.”

The MFAA was the result of a 1943 commission to protect cultural monuments – buildings, works of art, libraries, and records – which the US Government believed ‘constituted, in a broad sense, the heritage of the entire civilised world’.

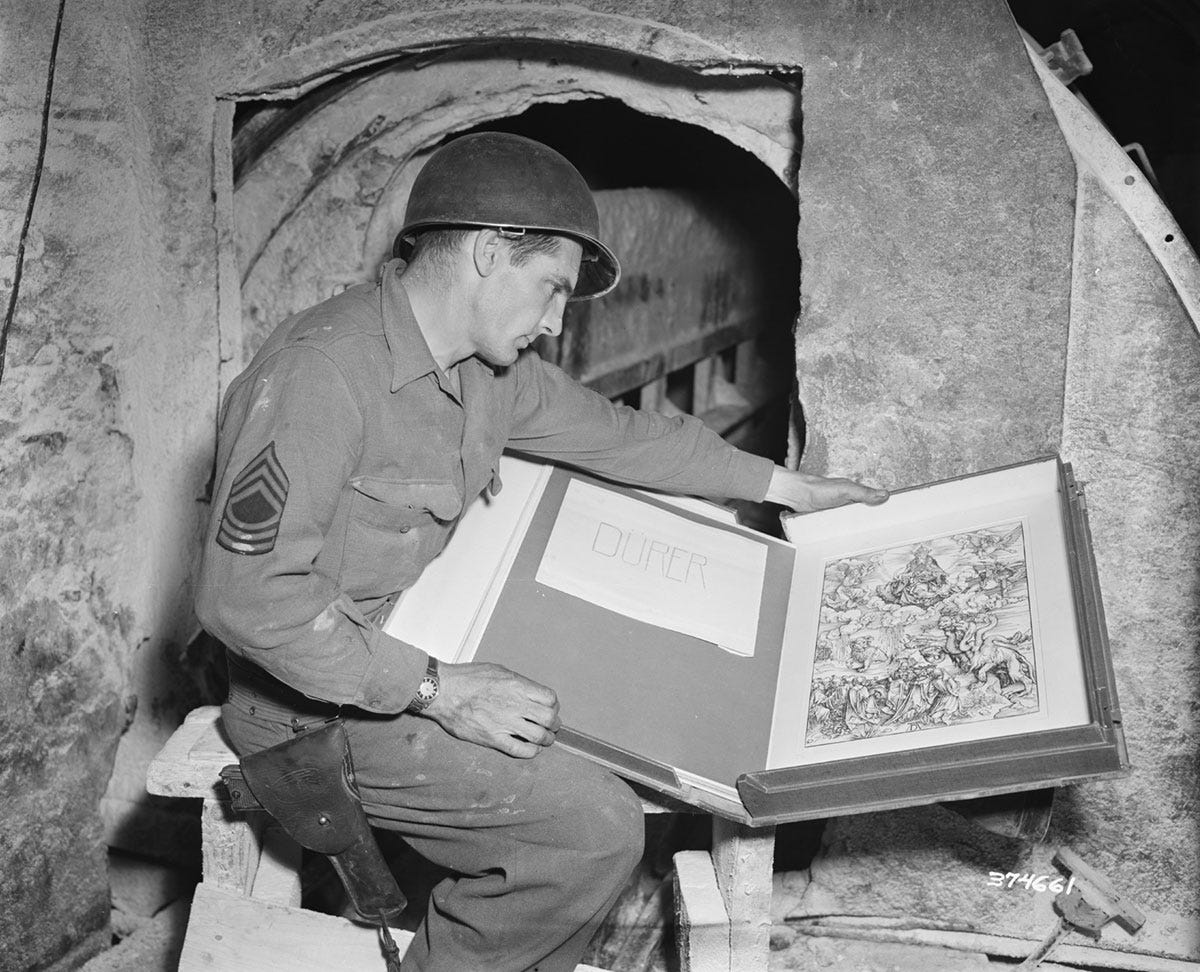

Starting in the 1930s, the Nazis began a two-pronged mission to seize what Hitler considered ‘degenerate’ art (by the likes of Kandinsky, Matisse, Munch, and Picasso), as well as what he considered exemplary artifacts (such as works by Botticelli, da Vinci, Rembrandt, and Vermeer). The former was sold or ‘disposed’ of, the latter intended to be installed in the ‘Führermuseum’ planned for his Austrian hometown. As World War II spread across Europe, so did the Nazi’s looting.

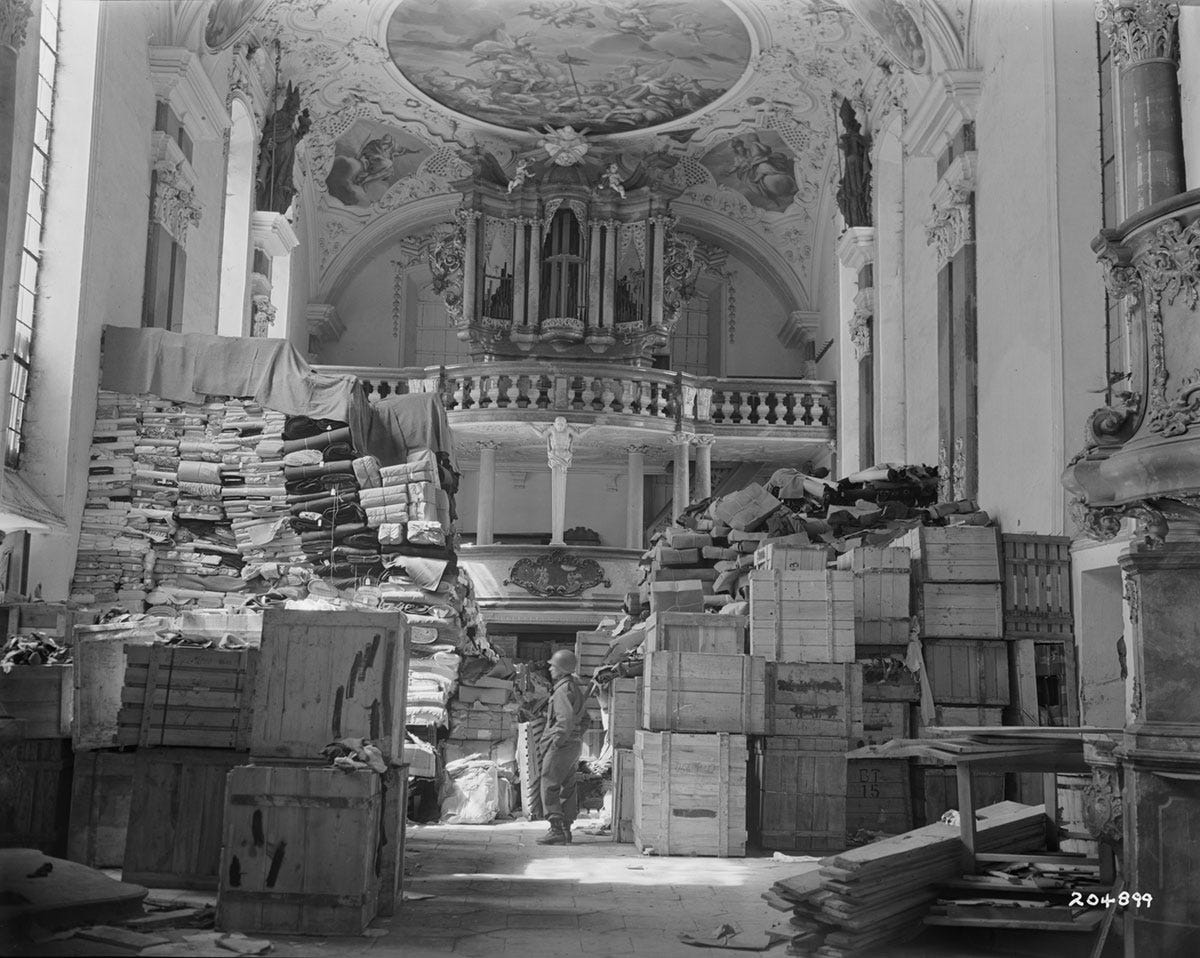

The MFAA recruited a special force of American and British museum directors, curators, art historians, and others who were attached to the civil affairs sections of the Allied armies. They helped evacuate artworks ahead of the Nazi’s advance and discovered hundreds of secret repositories where art looted at Hitler’s direction had already been stashed. That’s the part of the story played out by Clooney and co in ‘The Monuments Men’ film.

Due to the gender inequalities of the period, women were barred from working in combat roles and zones. But the Monuments Men and Women Foundation says their service was “instrumental” in the post-war effort.

You see, once the war was over, the task of cataloguing, identifying owners of, and returning the more than five million preserved and recovered artworks, sculptures, tapestries, fine furnishings, books and manuscripts, scrolls, church bells, religious relics, and stained glass, began.

“Monuments Women played a vital role in restitution efforts, serving at the central collecting points and at MFAA headquarters and satellite offices in various positions, [from] administrative support staff [to] intelligence specialists, and even collecting point directors,” the Foundation says.

Despite “limitations and regulations placed on women at that time” and being just a tiny minority of the 300+ MFAA section, the 27 Monuments Women “found ways to put their skills to use and were respected and appreciated by their male colleagues who worked right alongside them,” the Foundation says.

Among them were six British women:

Little is known about the biographies of Dignam, Bowie, and Hutchinson, other than that they worked in administrative and secretarial roles, transcribing notes and correspondence, and serving as typists for senior Monuments Men. (The Monuments Men and Women Foundation would welcome any further information.)

Jacka was a librarian working in north London before joining one of the MFAA headquarters in Bünde, Germany, where in 1947 she became Assistant Director under the office’s Head of Section. She helped coordinate the work of the men in the field, and organised transportation, including on at least one occasion personally escorting objects across the country. She eventually returned to her job as a librarian.

Westland was a member of the MFAA stationed in Düsseldorf, Germany, where she investigated claims for the repatriation of looted art. She also acted as an important link between archaeological institutions in London and Frankfurt. After her service, back in the UK, she became an expert in English furniture and textiles.

Bell was an art historian who began working as a research assistant for the British Ministry of Information during World War II, before being recruited for the MFAA, stationed at Bünde. She earned the rank of Major, the most senior woman at the headquarters, where she coordinated the day-to-day activity of the office and the men’s activity in the field (she was later succeeded by Jacka). Back in England, she married Quentin, the son of Vanessa Bell, and spent the rest of her life helping to preserve the cultural legacy of members of the Bloomsbury Group, including her aunt-in-law, Virgina Wolfe. She was the last known surviving member of the British MFAA. Her diaries from her time in Germany, as well as an oral history of her life, is held by the UK’s Imperial War Museum.

The Monuments Men and Women Foundation says it is "dedicated to spreading awareness and honouring all who served in the MFAA" and hopes that by "shedding new light about the Monuments Women" – including through profiles of them all alongside the men – "people can learn that they too were heroes in their own right, despite not being on the front lines".