Issue 63: the accidental archivist and his unrivalled folk customs collection

One man's mission to document the traditions that 'make up life for communities' across the British Isles.

Since he was young, David Rowe, 79, has been hearing claims that the folk traditions of Britain and Ireland are dying out.

From radio presenters (“or the wireless, as it was in those days”) on BBC’s ‘As I Roved Out’, who lamented the death of traditional music as they played folk songs recorded in the 1950s, to early folklorists’ scepticism over the authenticity of continuing celebrations and events (“some of them decided that if an event was flourishing, it must have been interfered with”).

But Rowe’s collection tells a different story: it’s an unrivalled longitudinal study of folklore and traditional arts that’s been 60 years in the making and is still growing.

“I have people say to me: ‘Oh, it’s lovely that you’re capturing these things before they die out’. Now, why would they die out when there are people that are living and breathing it?”

Sure, he’s seen changes: “Some of the events are now micro community based. In a village there may only be one or two people that still participate, but they have family and friends that live elsewhere who come in for the day.”

And there are a lot more tourists now: “I'm documenting more about the people that visit the events than the event itself these days. Their power [to attract people] is quite extraordinary.”

But dying out? “Far from it!”

Rowe – who is known as ‘Doc’ (a shortening of ‘doctor’, which was a lengthening of his initials, DR) – describes folklore and traditional arts as “all the things that make up life for communities. It is beliefs, rites of passage, legends, stories, it’s the superstitions, the songs, the dances, the rituals – all of which were created by real people. And that’s what excites me. At some point somebody created these things. It’s very special”.

Before his documenting and collecting became... "it could be seen as an obsession, but it's just part of my life", Rowe was aware of folk customs still being practiced in parts of Devon, in southwest England.

“I was a bit appalled that the BBC was telling me all these things – the song, the dance, the dialects – had died out, because I’d come across people on Dartmoor that sang and danced. My father was a broad Devon speaker.”

But his interest was really kickstarted in 1963 when he went to the May Day celebrations in Padstow, in Cornwall, southwest England, for the first time. “The event is absolutely extraordinary, very emotional.” He carried on going back for 10 years straight and most other years since.

However, after his first few visits, when he sought further information about its history and meaning, he was angered to read details in books and media that he knew to be wrong.

“So, I started documenting it, recording local people talking about the past, looking at the old photographs and using them as an aide memoire.” The result was a comprehensive record of people’s memories and first-hand experiences of MayDay in Padstow from the early 20th Century.

In 1973, Rowe went to Abbots Bromley, in Staffordshire, in the West Midlands of England, for the annual horn dance ceremony and found “the same passion, the same emotion, the same sense of history and locality that I was discovering in Padstow”. And likewise, he’s continued to visit, and to document the event, nearly every year since.

Rowe has a list of over 800 folk events and celebrations (or ‘calendar customs’ as they’re sometimes known) which take place across Britain and Ireland every year. He has visited and documented several hundred of them. But there’s no specific approach to prioritising where he goes.

Rather, his documenting has been driven by curiosity and serendipity, and by the freedom he enjoyed in the early decades – first as an art student, then in an educational media job with good wages and short working weeks, and later while squatting in the English linguistics seminar rooms at Sheffield University (“I can reveal that now, I don’t think they can touch me for it”) when he was a regular contributor and collaborator with its Centre for English Cultural Tradition and Language (“long since closed”).

“I was just off hitchhiking everywhere, with a camera and tape recorder, to find things. Somebody might give me a lift, and they would say ‘what are you up to?’ and I'd say my interest and they’d say ‘oh, you want to talk to my granddad’. So, I would go off and record their granddad or some such.

“I would just bump into people who might say ‘have you heard of…?’ and perhaps I hadn't – or I had – and they’d take me to it. It really was an extraordinary time. I’d go to an event in the middle of Lincolnshire and then someone would say ‘oh, so and so is getting married on Saturday, you going? Oh, you must go’, and I’d go and photograph their wedding three days later in Suffolk, and then somebody there would say ‘we're going off to X’ and then I'd go [with them] to Bristol two days later, because, well, I was just free.

“I was the only stranger at some of these places. They couldn’t imagine anyone would be interested in what they were doing. But because I wasn’t an academic, or a historian – because it was personal – they embraced me.

“It’s quite a privilege that I’ve been allowed to do all this.”

Rowe is fuzzy on the point at which his documenting and collecting morphed into an archive: “it was very unconscious […] I call myself an accidental archivist”. But he does remember a point in 1979 when “I suddenly realised – people were telling me – that what I had was so different to other collections. No one had done the serial collecting of events every year.”

Today his collection is housed in Whitby, in the north of England, in a former pharmaceutical unit which boasts cool, dark, and dry conditions – perfect for an archive. A group of supporters chips in regular small donations to help him cover the rent.

More recently, 1,125 people have contributed £66,063 (at the time of publication) to a Crowdfunder to help professionally digitise the archive’s film and video material, alongside the production of a documentary about Rowe and his work by Fifth Column Films.

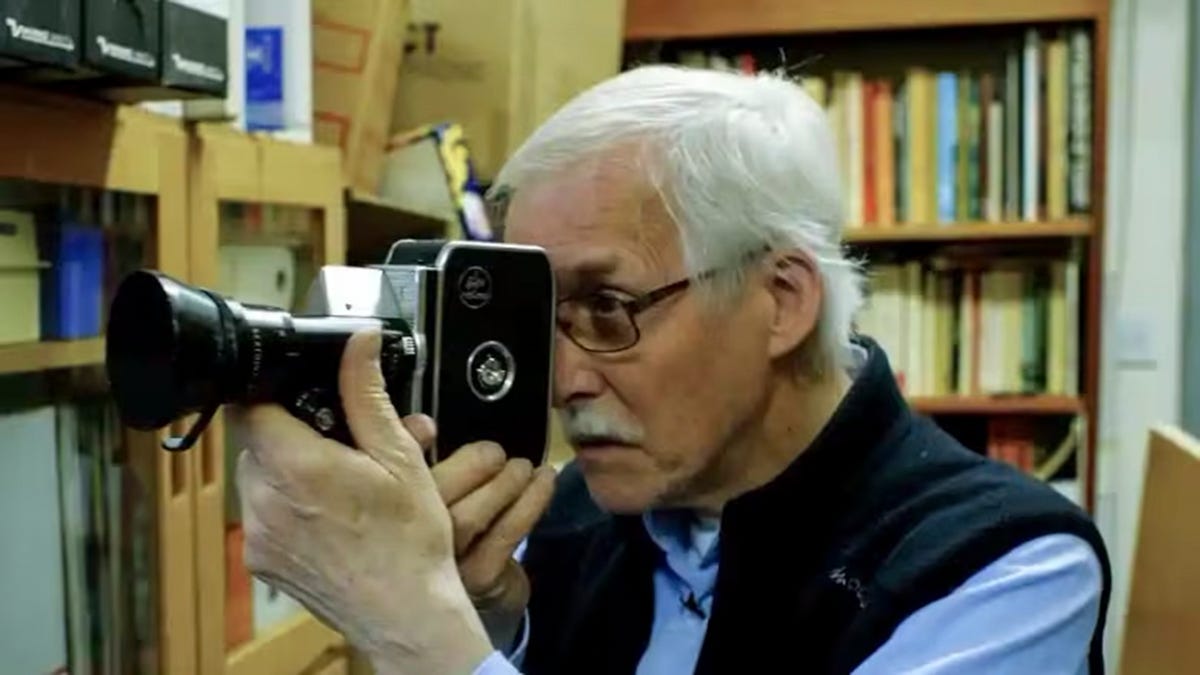

Rowe is a reluctant film subject (“I've found it difficult having a camera on me because it’s usually the other way around”) and uneasy in the spotlight the Crowdfunder’s success has shone on him.

“I don’t really like, what would you call it, the ‘celebrity status’, I suppose. I’d sooner people applaud what they see or hear from the collection, rather than me. The importance is the material and the people recorded, nothing to do with its quantity or that I did it.”

But it’s impossible to talk about Rowe’s collection and its significance without talking about its size.

Off the top of his head, Rowe says: “there's 42,000 black and white negatives; thousands and thousands of transparencies; 42 hard drives [of digital images and footage]; audio tapes in every format from open reel through to cassette, DATs, mini disc and now digital – there’s 4,500-5,000 cassettes; 17,000 books and pamphlets”.

Plus, there’s the film, VHS and mini-DV footage being digitised thanks to the Crowdfunder. This alone is thousands of hours’ worth, but such is the scale of Rowe’s archive, it represents just 2-3% of the total collection.

The digitisation, and in turn, the long-term protection, of the full archive, is something Rowe has been thinking about more often lately. Last year, he got seriously ill for the first time in his life, and admits “suddenly, you’ve got to realise, you’re nearly 80…”.

He tells me there are “discussions going on” about potential routes to securing the archive’s future, and while he feels “optimistic”, the responsibility “to make sure this stuff stays together and is kept perfectly” weighs heavily. He’s seen too many other collections dispersed and fragmented due to funding cuts and closures over the years. “If everything was digitised then I could sleep well at night.”

In the meantime, the collecting will go on: “In 2020, when I was 75, I thought it would be good to revisit as many of [the events] as I can. I had a calendar all marked out […] I managed to achieve a few and then they announced the lockdown.

“Now I’m thinking, 80 is [an important age] as well, so maybe next year I can start again.”