Writing, for posterity

How time can render the everyday extraordinary. (Historians of the future will thank you.)

It’s been a tough few weeks for women in the UK. We’ve once again been reminded about the ways in which simply being women impacts our safety and our freedom.

Even worse, we’ve been shown how, sometimes, the people we should be able to go to for help are in fact the perpetrators of abuse against us.

So, it was in ‘you-gotta-laugh-or-you’ll-cry’ spirit that I gave a big like to Madeline Odent's tweet on Sunday (which was census day in the UK).

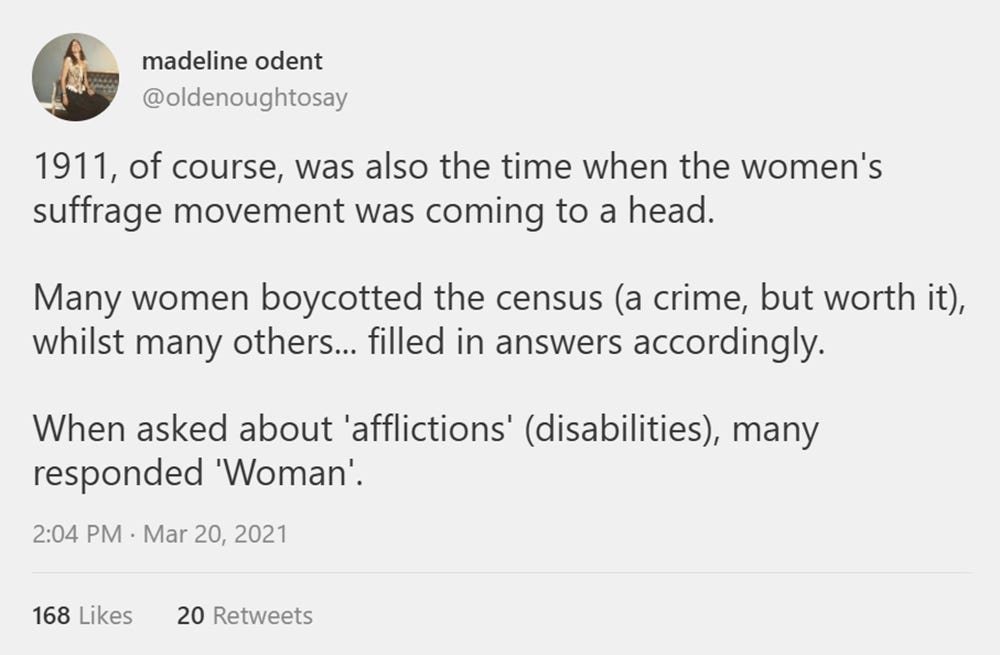

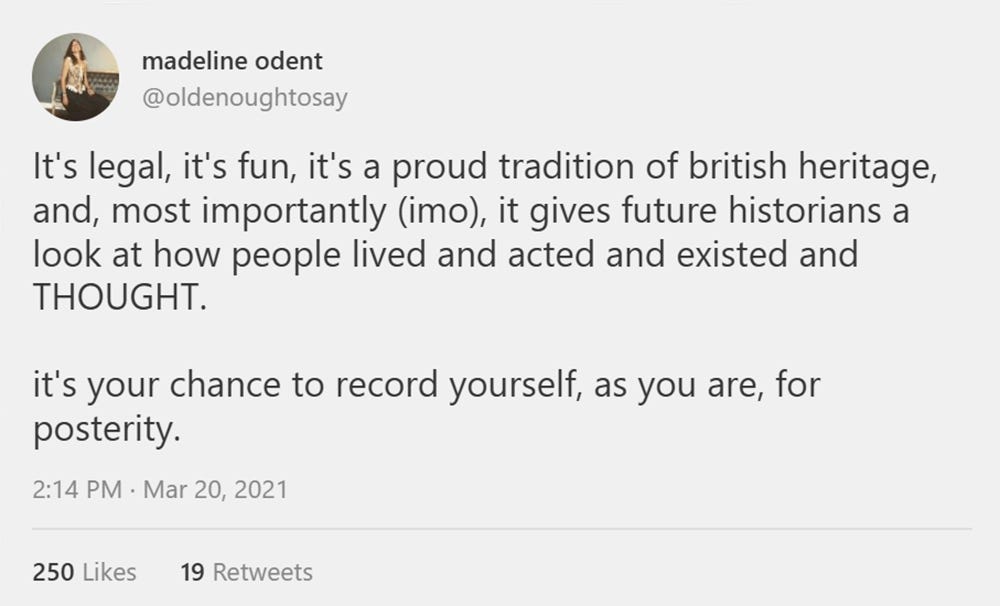

Odent published a whole thread about the amusing ways "Brits have been trolling the census for literally as long as there has been a census".

But what really struck me was her penultimate post:

It struck me because it linked to a few different trains of thought that have been circling in my head recently.

In December 2020, Shelley Hepworth wrote in The Guardian about the transitory nature of digital communication and social media, and the risk of important stories being lost in cyberspace.

“No one knew (Anne) Frank’s diary would be worth preserving until after she was gone and I wonder about the stories we’ll miss out on when those kinds of records are kept on password-protected phones and computers we don’t know to look for.”

That then reminded me of an article I read, probably around 10 years ago (but damned if I can find it again now!) about how, despite great advances in technology and the proliferation of digital platforms to chronicle our daily lives, pen/cil and paper is still one of the most reliable ways of recording and preserving information.

Paper can last centuries, but electronic records can be rendered useless through digital obsolescence in as little as 10-20 years if they are not continually upgraded or migrated to new formats. (Remember Myspace?!)

You see, living through this past 12 months – marked by pandemic and protest, the division caused by Brexit, the fall of Trump and the emboldening of the right, and the ongoing fight for racial and social equality – has had me thinking a lot about the value of writing and record-keeping.

Not posting updates on social media, or even doing morning pages (although I’m definitely thinking analogue rather than digital) but capturing our observations and opinions for posterity.

Because – particularly for women – if we don’t tell our own stories, record our own histories, few others will.

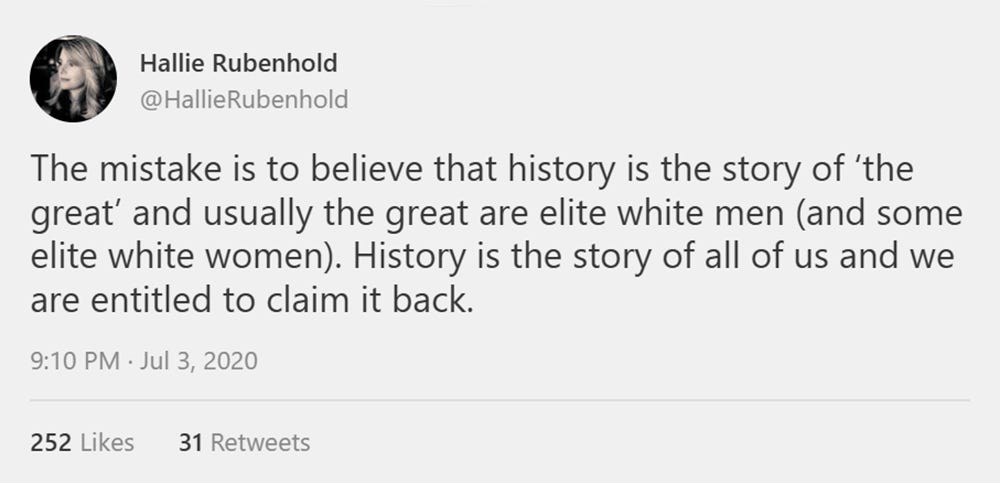

As author Hallie Rubenhold puts it:

Those of you who have read Rubenhold’s incredible book, ‘The Five: The Untold Lives of the Women Killed by Jack the Ripper’, (and if you haven’t, I urge you to!) won’t be surprised to hear she’s a vocal advocate for social history, and a critic of what she calls ‘Great Man’ history. (She’s also “a census nerd”.)

In an essay titled ‘The Problem With Great Men’, she explained how:

“Great Man’s influence in the public sphere has been to reduce the vast expanse of history into a handful of notable personalities and important dates. It gives the impression that history happened to someone else, to a chosen collection of ‘heroes’.”

The antidote to Great Man history, Rubenhold says, is social history, and its ability to “take us through the backdoor into a subject, rather than predictably entering through the great hall”.

“Social history is egalitarian; the evidence left behind by any individual regardless of rank, class, creed, colour or gender is used to help us understand the past […]

“What social history offers us is not a wide-angle lens, but a microscope. It allows us to define the small more clearly by examining the person rather than the event. Social history permits an intimacy between the past and the present. The people whose lives became entangled in a war, or the enactment of a law, get to tell you how it impacted them personally. It examines how our ancestors understood their feelings of love, grief, friendship, shame, fear, loneliness and failure. It looks at the physical fabric of their lives; their homes, their clothes, their food and the systems and structures that ordered their daily existence. It tells us what they thought of their circumstances and how they viewed one another. Most importantly, it encourages us to consider how much of their values and their world we have inherited.”

It’s also pertinent to note that social history “has been the primary tool through which women's voices and experiences have been recovered”, Rubenhold says.

So, I say: treat yourself to a lovely notebook and pen, and write. Write for creativity or productivity, write for release or recovery, but write for posterity, too.