Issue 53: how ancient Libyan ruins ended up in the grounds of Windsor Castle

Warrington had high hopes for the reception he'd receive; but alas, it wasn’t to be.

UK Prime Minister Rishi Sunak caused a diplomatic incident this week by cancelling a meeting with the Greek Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis. The reason for the cancellation? Mitsotakis refused to keep quiet about the Parthenon sculptures. It’s part of a saga that’s been rumbling on pretty much even since Thomas Bruce, the 7th Earl of Elgin, removed the 30+ stone carvings in the early 1800s. Opinion is divided about the ethics of the ‘Elgin marbles’ remaining in the British Museum versus returning them to Athens.

Interestingly, there’s a lesser-known collection of stones that were brought to England in the same year as the Parthenon sculptures were sold to our government, which now form part of a mock ruin in the grounds of Windsor Castle.

I’ve written before about the trend which began in the 18th Century for English landscape gardens punctuated with architectural follies (often in the form of ruins) to delight visitors.

But that wasn’t the original intention for the subject of today’s newsletter. The acquirer of these stones had much higher hopes; but alas, it wasn’t to be.

Let’s set the scene: the year is 1816 and the British officer Colonel Hanmer Warrington is on the Mediterranean coast of what was then Ottoman Libya. He’s visiting the Roman ruins of Leptis Magna.

The city of Leptis was founded as early as the 7th Century BC and was at its height under the rule of Emperor Septimius Severus (193-211 AD), who was responsible for an ambitious building programme. But over the centuries – through changes in rule, natural disasters, and invasion – the site fell into ruin. The French had already taken some of the buildings’ columns in the 17th Century and by the time Warrington arrived, the locals were using the site as a quarry.

A watercolour painted by Warrington’s travel companion, artist Augustus Earle, shows the area being overtaken by sand.

Perhaps with visions of Parthenon sculpture-levels of fame and gratitude in his head, Warrington convinced the Ottoman governor to allow him to salvage the ruins and take them to the UK.

The locals vehemently opposed the agreement, obstructing transport of the stones to Warrington’s waiting ships. Apparently three large columns abandoned in the tussle still lie on the beach to this day.

As writer and podcaster Paul Cooper describes in an article in The Atlantic, Warrington arrived home in 1817 with ‘25 pedestals, 22 granite columns, 15 marble columns, 10 capitals, 10 pieces of cornice, seven loose slabs, five inscribed slabs, and various fragments of figure sculpture’.

But unfortunately, nobody really cared. Cooper quotes the British Museum as being not “at all impressed or convinced of the value, either aesthetic or intrinsic, of the cargo”.

And so, the Leptis Magna antiquities languished in the museum forecourt while it was considered what to do with them. Eventually, in 1826, they were given to royal architect Jeffry Wyatville.

Wyatville erected them on the south side of Virgina Water, a man-made lake in the sprawling 6,400hectare (15,800acre) Windsor Great Park, part of the royal estate that’s also home to Windsor Castle. New columns that had been distressed to look ancient were used to complete the scene.

The mock ruin was dubbed ‘The Temple of Augustus’, perhaps after the full name of the then King George IV: George Augustus Frederick.

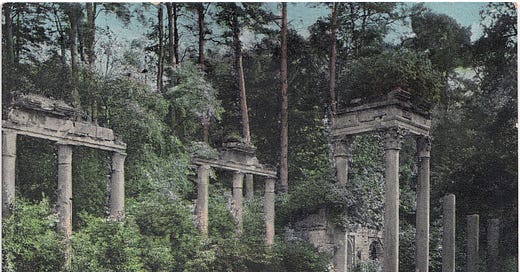

The site (which was Grade II* listed in 1986) is arranged in three groups, covering an area around 70metres long by 30metres wide. The columns are about 9metres tall.

One group consists of a semi-circle of Roman marble columns mainly with Corinthian capitals (that’s the decorative bit at the top of the column) and some sections of entablature (that’s the horizontal bit that ‘joins’ two columns together). A few feet beyond the columns, Wyatville built a wall with a semi-circular niche, adding to the ‘temple’ impression.

A road bridge with archway underneath (which King George IV used to drive his carriage through) divides this group from the other two. Both sides of the bridge feature bands of stone fragments from Leptis Magna.

The other two groups are a series of Roman red and grey granite columns arranged in two parallel colonnades with some shafts of column laid on the ground to further the ‘ruin’ effect. Some of the columns feature Corinthian or plumed capitals and some have entablature above.

Historic England describes the site as “probably the most impressive artificial ruin erected in this country”.

(A couple of images that I don’t have budget to licence which might help you get a better sense of the site: looking from the lake towards the parallel colonnades, with the bridge in the distance; and looking through the bridge arch to the semi-circular ruins on the other side.)

And there’s a modern irony to the story of Warrington’s plunder, taken in hope of emulating the Parthenon sculptures. Last year, a London-based Libyan lawyer requested the Crown Estate return the ruins to Libya. (Leptis Magna was designated a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1982.)

Mohamed Shaban said in a video statement in April 2022: "The time of the empire has elapsed [...] There are international conventions that say items of cultural value have to be returned to their people."