Issue 51: a social history of 1920s London (part 3)

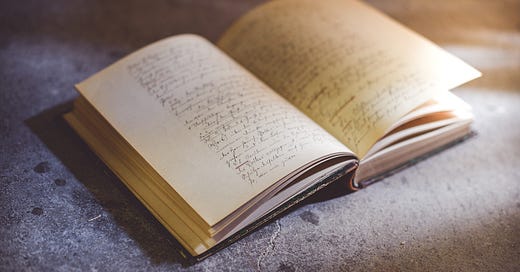

A window onto life for a young woman living in the capital 100 years ago, as described in her diary.

An intermittent series told through the 1923 diary of 17-year-old Londoner, Lily*, who lived in the north of the capital and worked at her father’s shop in the east. Who loved art, fashion, and dancing, and who was determined to enjoy herself while she was young.

Her diary is housed at the Bishopsgate Institute in east London, part of the 17,000+ collection of The Great Diary Project, founded in 2007.

Read the previous instalment:

We pick back up with Lily in the weeks after her mother’s death. She is still devastated, and frequently questions the point of life.

“I’m so miserable – if this is life I don’t want to live at all – what is life at most?”

“Oh rotten world, rotten life, rotten rotten everything.”

With her mother gone, Lily now finds herself thrust into the role of responsible female of the family, with all the domestic duties that entails.

“I’m at home in the mornings till about 1.30 – making the beds, cleaning and dusting round, shopping, and making the children dinner. Then I go to business, make father’s dinner, and see to books and correspondence. By this time it’s about 5, so I make tea and rush home – rush, rush all rush… [My sister] gets home about 6 or thereabouts, so I have dinner ready for her again. Three dinners a day – oh what a life.”

She is of mixed mind about the whole situation. Fluctuating between bemoaning the monotony and neverending-ness of it all, and feeling proud that she is doing her “duty”:

“I’ve made a discovery little book – there’s no feeling more delicious than knowing one has done one’s duty… it’s a nicer feeling than dancing or being popular. It’s nice to be of some use not just to gad about.”

Lily is in a period of mourning. She must wear black for a year. That jade jumper she was knitting? It’s finished now, but she’s had to dye it black. And she’s not happy about it.

“It’s so depressing – oh why do we have to dress to show people that we’ve had a loss? They don’t sympathise, and we feel it without.”

But her observance of religious tradition doesn’t stop her fantasising after coloured clothes.

“I was reading a illustrated article today on summer fashions for this season. How my heart ached – such delicious pinks and blues and lavenders and creams etc in organza, georgette, voile [...] I do so love pretty clothes and bright colours. All black is so horrible.”

“Oh I feel that when I may wear colours again I’ll have a green hat, red shoes, purple jumper and yellow skirt! The effect would be striking, I admit, but I wouldn’t care much – I want to wear colour.”

We also hear how one of Lily’s sisters has gone to a séance in an attempt to make contact with their mother.

Following the First World War – when so many families experienced loss – interest in spiritualism surged dramatically.

“My sister went to a séance last week and is going again tonight. […] The place was crowded and the medium sits in the corner with a crystal... She looked round the room and picked out about half a dozen people. She pointed to one lady and said she could see a child’s head on her should and said ‘have you lost her recently?’ It happened to be the lady’s daughter. The medium described her perfectly. [My sister] thought it was possibly pre-arranged, but the medium turned to her! saying ‘I see a woman next to you, a tall woman – is it your mother?’ [My sister] replied that it was. The medium then described mother and said ‘She suffered a lot, you must not grieve, she is better now. If you had known what was the matter with her you’d have seen to it before – and might have had her a few more years – but you must not grieve now. She is at rest and has no more pain’.”

“It’s so bewildering. I don’t know whether we can believe it to be genuine… Of course we hope that there is a hereafter, another life – and that the spirits of our lost ones can come to us – but the thought that we walk about surrounded by ghosts does frighten one.”

Towards the end of the summer, Lily’s spirits are lifted. She’s offered the opportunity to visit an old family friend in Reading – where her family had lived for nearly two years during the war – with her younger siblings.

“I’m so thrilled, so elated, it doesn’t seem possible. […] I’m counting the days til I can go. I’m so excited.”

Out of London and away from the sad memories associated with home, she is transformed, even breaking out of her black mourning wardrobe.

“When I went out blackberrying yesterday I put on a red dress up to my knees and sallied forth. I went out to enjoy myself and romp about like a big kid. The wind did blow, but did I care? Not I – I ran about and rolled down hills like any kid.”

She used a camera for the first time on 17 August, but the results were “rather disappointing”.

“All the snaps are blank except one, and that’s not much use! I’ll take more this afternoon – hope it’s better.”

The following day she “had snaps taken amongst the cows in a field”.

At the end of her week away, Lily reflected:

“When I arrived here I was a dressed up fool and now… what a difference. One would hardly recognise me. I’m out in the open all day and have got so brown – like a ni**er.” [Asterisks are mine!]

Back in London in the autumn, Lily was out and about in her fox fur – “it’s a beautiful fur, soft and silky with a bushy tail” – when she encountered a little problem.

“I had it over my arm as it wasn’t cold. Suddenly I heard barking and a dog started running round my feet. I screamed and was really alarmed – then I saw what he was after – it was the fur. Recognised in him a long lost brother perhaps… I was glad when the owner called him off.”

One other thing it’s worth noting, is Lily’s observations on the differences – at least in terms of societal expectations – between young women and men.

Despite admitting that “[o]ften out of devilry I’d go over the park with fellows not caring how late it was”, that she was “reckless”, and how she’d “often feel tempted to say ‘dash it all – why can’t I have my fling?’”, she said that something always stopped her “from being such a fool”. That when boys tried to kiss her “it would frighten me and wake me to realise what I was doing” – her devilry, her recklessness.

But boys? “Boys have such bestial desires.”

“A girl has to be nice and pure and all the rest of it – and the men??? [They are] so like the lower order of animals, very little difference. Perhaps the men are more civilised – having education and all the rest of it – but the ideas and thoughts as far as one subject is concerned is on the same level as the other animals. […] I’ve always been decent. I wouldn’t let a boy kiss me – never would – and to think of it that men should be so beastly.”

She recounts a tale from a trip to Brighton the year before when she met “the only one Jewish boy in the whole place” and spent the day with him. In the evening:

“[H]e took me to some place where there wasn’t a soul around. […] He put his arm around me and started to kiss me – and tried other things. This child wasn’t having any – I told him to quit and left him. He told me he thought me an innocent and wanted to teach me things.”

As he left, he warned her to take care, as the next boy might have ‘a weaker will than me’.

Read part 4 of 4:

* Lily isn’t her real name. Given the diary’s author (1905-1993) isn’t that long passed, I’ve agreed to change her name and anonymise some of the finer details she wrote about, to protect the privacy of her living relatives.