Issue 44: the influence of medievalism on the Suffragettes

And how a love of Chaucer could have inspired one of the most infamous moments of the votes for women campaign.

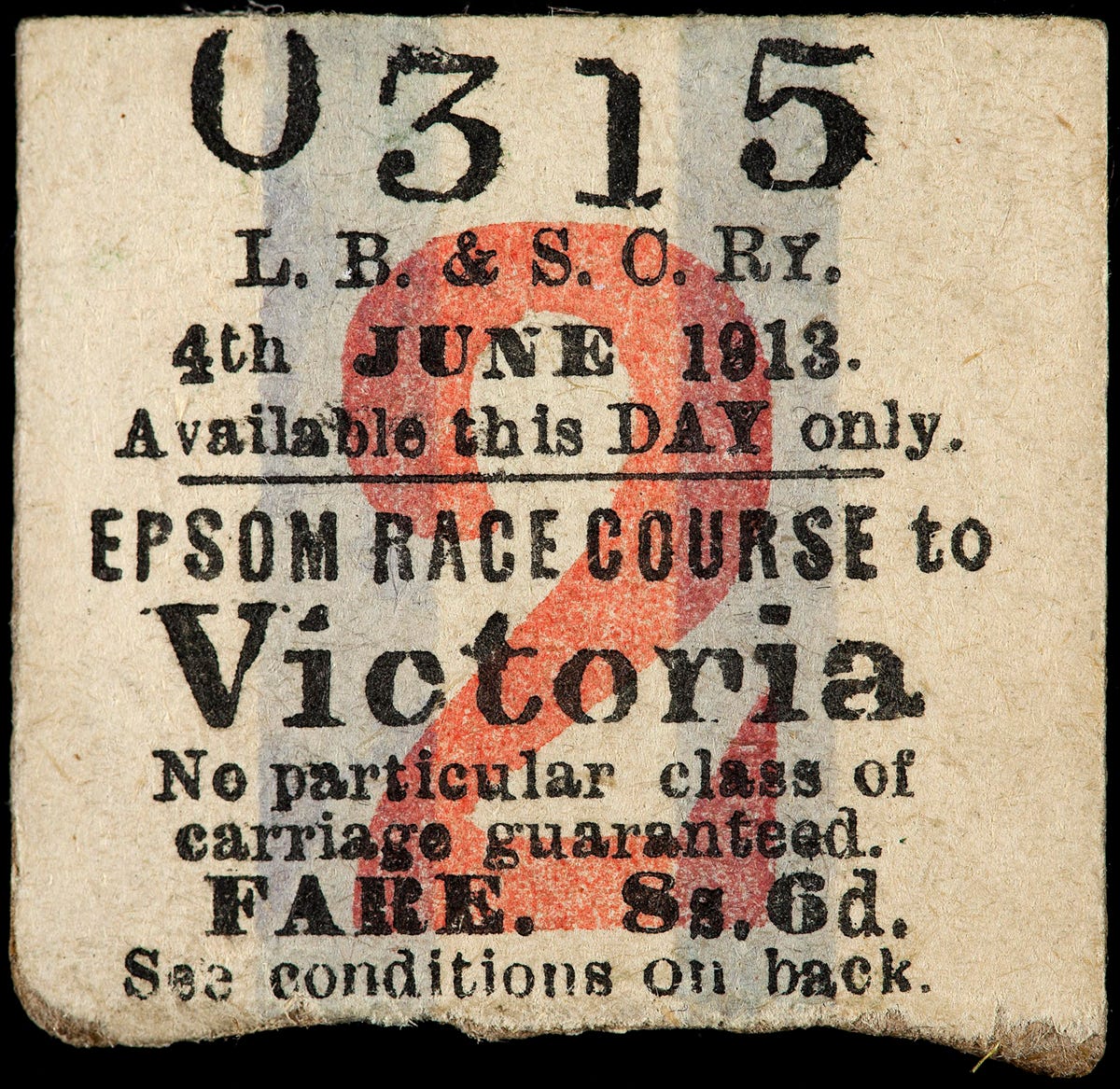

No one can say for sure what was the ultimate intention of Emily Wilding Davison when, on 4 June 1913, she stepped onto the racetrack at Epsom, in Surrey, UK.

Was it an act of self-sacrifice or a tragic accident?

Regardless, her actions that day, ‘Derby Day’ – when she reached for the bridle of the horse, Anmer, which was owned by King George V, and was fatally injured – made her a martyr for the fight for women’s suffrage.

Davison was a Suffragette, part of the militant group that was campaigning for the right for women to vote. Their motto was “deeds not words”. She was arrested and jailed multiple times – and brutally force-fed while in prison – for offences including public disturbance and vandalism.

But as I recently learned, Davison’s interest in the suffrage movement was, at least in part, inspired by her love of medievalism. And her commitment to achieving votes for women wasn’t about creating progressive new rights, but in fact a desire to return to the way things had been in the past.

As Dr Janina Ramirez explains in her book, ‘Femina, A New History Of The Middle Ages, Through the Women Witten Out Of It’:

“It's a widely held view that women's empowerment began in the twentieth century, when the 'votes for women' movement finally gave voice to the 'second sex'. […] But Emily Wilding Davison didn't think the Suffragettes were breaking new ground. For her, they were attacking a recent phenomenon of oppression. She wanted to return to an earlier time which she believed was populated by powerful women. In the medieval period she saw a model that challenged the pattern of misogyny embedded in the modern age.”

The early 20th Century in the UK was a time of widespread opposition to women’s suffrage. In an article for the British Library, retired teacher, academic, and author, Dr Julia Bush, explains that anti-suffragism was rooted in popular prejudices. Opponents feared an increase in women’s rights would subvert the entire social order by undermining the gendered foundations of domestic life.

But as Carolyn P Collette, Professor Emeritus of English and Medieval Studies at Mount Holyoke College in Massachusetts, USA, writes, the Suffragettes believed this attitude towards women, and their domestic status, hadn’t always been the case:

“In the militant suffrage view of history, modern women, forced into an apolitical social existence, were more constrained and restricted than women of earlier ages, particularly the Middle Ages, a period to which they looked for examples of powerful women and in which they found models of an active faith.”

Joan of Arc was a popular symbol of the Suffragettes. Indeed, one of their mottos – which featured prominently on a banner at the funeral of Emily Wilding Davison – “Fight on and God will give the victory” is a variation of one of Joan of Arc’s famous sayings: “In the name of God the soldiers will fight and God will give the victory”.

For Davison, the connection went even deeper than the iconic Patron Saint of France.

Emily Wilding Davison was highly educated. She’d achieved first-class honours in English literature at St Hugh’s College, Oxford, but was unable to graduate because Oxford University didn’t allow women to earn degrees until 1920.

Despite lack of official academic recognition, she wrote often – producing essays (published and unpublished) and letters in support of women’s suffrage sent to various daily newspapers. The body of work she left behind reveals the influence of medievalism in her thinking and her actions.

Collette, who has studied and edited Davison’s personal papers, says the Suffragette “invoked both medieval history and faith in God as part of the armour of her militancy”.

“A fundamental, recurrent theme of Victorian medievalism [was] an assertion that the medieval English church had been a potent force for community of all classes and people, and could be a model for the modern era.”

One of Davison’s most significant influences was her lifelong love of Chaucer, and in particular, an affinity with Emelye in the ‘Knight’s Tale’. Friends and classmates referred to Davison as “the faire Emelye”, and she occasionally signed off letters using the name into her adulthood.

Collette says the story “offered a paradigm of the resistant Amazons, that is, of justice-seeking women who demand attention from the powerful”.

“It is a short step from reading Chaucer’s Emelye as an Amazon imprisoned, longing for freedom, denied agency over herself and her status, to connecting her with the suffragist complaints about the constraints English women faced at the beginning of the twentieth century.”

Moreover, Collette says, the ‘Knight’s Tale’ may provide “an intriguing analogy by which to understand the significance of that day at Epsom”.

“[It] evokes a major scene in the ‘Knight’s Tale’ where a group of Theban […] widows seek the attention of Theseus, duke of Athens, representative of power and authority in the tale, by reaching up to seize the bridle of his horse. Davison […] raising her arms up and outward towards Anmer’s head invites the thought that it was her intention to replicate the gesture of the Theban widows in the ‘Knight’s Tale’ in order to achieve a similar purpose: to redirect the flow of power and authority, to claim attention for those suffering injustice, left without agency or voice […]

“Driven by anger, frustration and an overwhelming sense of the justice of her cause, did Emily Davison strive to transform literature into life?”

Emily Wildling Davison died on 8 June 1913 from the injuries she’d sustained on the Epsom racetrack four days earlier. She never regained consciousness after the collision with Anmer. 20,000 people attended her funeral, which was said to be the biggest ceremony for a non-royal in UK history.

It would be another five years before the Representation of the People Act 1918 granted some UK women the right to vote – but only those aged over 30 who met a property qualification. It wasn’t until 1928 that the Equal Franchise Act gave UK women the vote on parity with men.