Issue 36: the man who democratised the colour purple

How my favourite colour is linked to one of my favourite drinks, and how its discovery broke new ground in fashion and science.

Look up attributes associated with the colour purple, and you’ll find terms such as ‘royalty’, ‘wealth’, and ‘power’.

That’s because, for thousands of years, the colour purple was so labour-intensive to manufacture, that only the richest people could afford it.

The original purple dye is named after the Phoenician city of Tyre (in present-day Lebanon), and though records vary, it is thought to have been discovered some time between the 16th and 12th centuries BC. Known as Tyrian purple, it is derived from the mucous of sea snails of the Muricidae family.

It took thousands of snails to produce even a single gram of purple dye. As such, its use and wear was restricted to the highest echelons of society (sometimes, allegedly, enforced by legislation!).

And besides a few plant-based dyes made from lichen or indigo – which couldn’t produce a vivid colour and faded quickly – that was how it was; until the mid-19th Century in England.

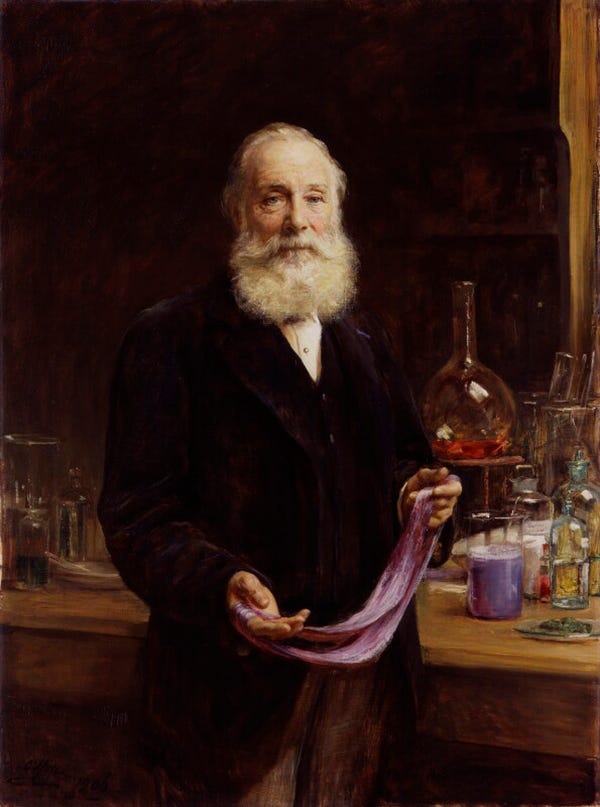

Enter William Henry Perkin (1838-1907): an 18-year-old chemistry research assistant who was seeking to solve the problem of another expensive and difficult to acquire ingredient.

In the spring of 1856, Perkin set himself the challenge of synthesising quinine, an antimalarial, which at that time was derived solely from the bark of the Cinchona, or ‘fever’, tree, native to the eastern slopes of the Andes, South America.

(Quinine is a key ingredient in tonic water, of gin and tonic fame; one well regarded manufacturer of which is Fever Tree.)

In his home laboratory on Cable Street in east London, Perkin’s attempt to oxidise the compound aniline (a colourless aromatic oil derived from coal tar) to obtain quinine, was unsuccessful. His beakers were left with just a dark sludge – no quinine.

But when Perkin tried to clean the beakers using ethanol, he discovered something unexpected and amazing. His cloths were stained a vibrant purple colour.

He named the colour mauve and the dye mauveine, and on 26 August 1856, was granted a patent for 'a new colouring matter for dyeing with a lilac or purple colour stuffs of silk, cotton, wool, or other materials’.

Perkin had created the world’s first synthetic dye. It marked the beginning of a colourful new era in the fashion industry, and the establishment of the chemical-pharmaceutical industry. Coal tar dyes and derivatives would go on to have many medicinal uses – from staining cells to study under a microscope, to the development of chemotherapy, and the discovery of the tuberculosis bacillus.

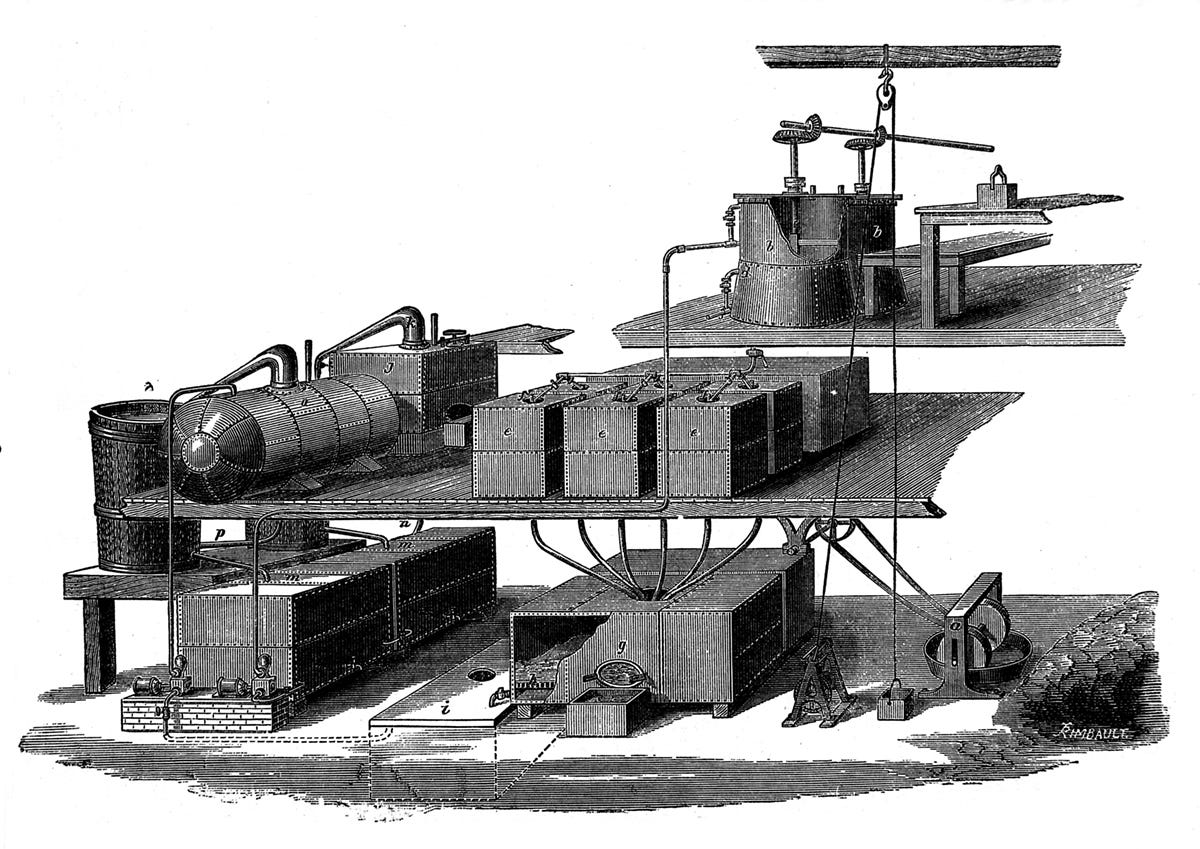

Shrewdly spotting an opportunity, Perkin decided not to return to his lab assistant job. Instead, in 1857 – supported by his father and brother – he set up a factory on the banks of the Grand Union Canal in Greenford, west London, for the mass-manufacture of his important new dye.

Soon, vibrant, purple-coloured clothes were available at affordable prices to the masses. Perkin had democratised the colour purple, and it became the height of fashion in London and Paris in the late 1850s to early 1860s.

In the 10 September 1859 edition of ‘All the Year Round’ magazine, edited by Charles Dickens, mauve was described as:

“…rich and pure, and fit for anything; be it fan, slipper, gown, ribbon, handkerchief, tie or glove. It will lend lustre to the soft changeless twilight of ladies’ eyes – it will take any shape to find an excuse to flutter round her cheek – to cling (as the wind blows it) up to her lips – to kiss her foot – to whisper at her ear. O Perkin’s purple, thou art a lucky and a favoured colour.”

Perkin would go on to create further synthetic dyes in sought-after colours, including the turquoise-like Perkin's Green and Alizarin, a vivid red previously only derived from the madder plant. It has been said that the canal beside his factory turned a different colour every week depending on which dye was being manufactured.

In 1874, at the age of only 36, Perkin sold his factory. He dedicated the rest of his life to research in his private laboratory.

He was knighted in 1906 on the 50th anniversary of his discovery of mauve.