Issue 30: how scientists tried to save the Loch Ness monster

A pair of stories about irregularities in the species classification record.

Last month, the Official Loch Ness Monster Sightings Register recorded its sixth official sighting of 2022.

On 11 October at 5.24pm, a mother and daughter noticed "a long break" in otherwise still water about 180 metres offshore. As they watched, "a black lump” appeared for approximately 30 seconds before disappearing under the water. After another 30 seconds, it resurfaced for a short time before disappearing again.

The pair described it as "boxy in shape" and about the size of a football. It didn't "swim", but rather "bobbed" above the waterline.

It takes the total number of ‘verified’ Nessie sightings to 1,143, according to the Register.

The Loch Ness monster is what’s known as a cryptid: an animal that’s been claimed – but never proven – to exist.

Believers say the first sighting dates back to 565, when Columba, an Irish abbot and missionary (who would later be declared a saint) used ‘prayer to repulse the aquatic monster’.

The most famous recorded sighting is the April 1934 photograph allegedly taken by a doctor named Robert Wilson, and known as ‘the surgeon’s photo’. However, it’s now widely believed to be a hoax (as reported by The Telegraph in 1975 and later by the Daily Mirror and Daily Mail in 1994).

But as the saying goes, ‘absence of evidence is not evidence of absence’, and it’s in that spirit that we come to the subject of this fortnight’s newsletter.

A few years ago, I had a conversation with a scientist at the Natural History Museum. He told me that the Loch Ness monster is one of only two scientifically described species that doesn't have a type specimen.

A type specimen is the representative of a species which is used to describe and name it.

The Loch Ness monster was given a scientific name in the journal ‘Nature’ on December 11, 1975, in an effort to protect it.

Sir Peter Scott and Robert Rines wrote:

“The Conservation of Wild Creatures and Wild Plants Act 1795 provides the best way of giving full protection to any animal whose survival is threatened. To be included, an animal should be given a common name and a scientific name. For the Nessie or Loch Ness monster, this would require a formal description, even though the creature's relationship with known species, and even the taxonomic class to which it belongs, remains in doubt.”

They argued that it was better to be safe than sorry, and, citing photographs and sonar images as evidence of Nessie's existence, they proposed the name Nessiteras rhombopteryx.

It combines the name of the loch with the Greek word for wonder (teras or teratos), and the Greek for diamond shape (rhombos) and fin (pteryx), thus: ‘the Ness monster with the diamond shaped fin’.

Other than Nessie, the only other species without a type specimen is us – Homo sapiens.

Another anomaly: the bird that’s not all there

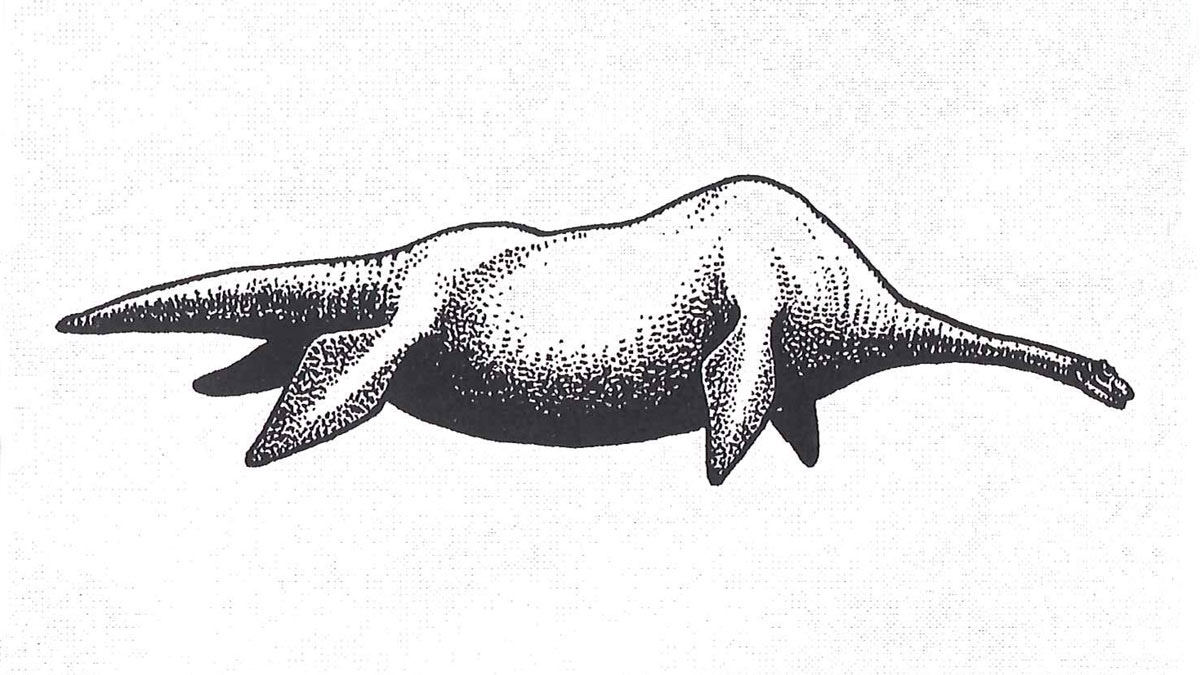

Before European scientists had seen them in the living flesh, birds of paradise were thought to have no legs.

According to the Papuans who traded them with neighbouring islands (and in turn, European explorers) the birds spent their lives floating high in the sky, feeding on dew. That's how they got their name – they were birds of the gods, birds of paradise. It was only when they died that they fell to earth and could be collected.

But the truth was that because the birds were prized for their colourful and elaborate plumage, their legs were considered unimportant and so were cut off.

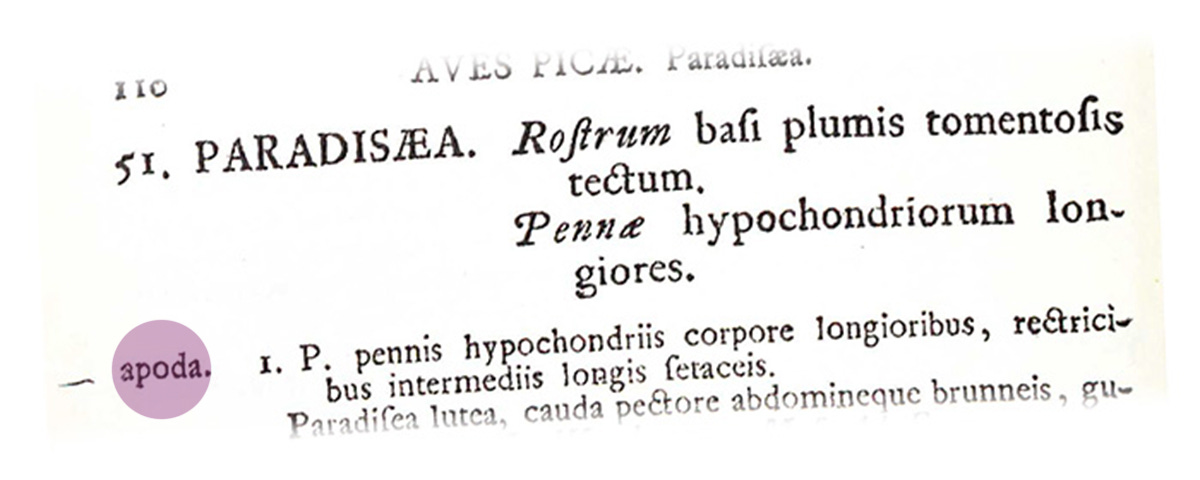

A legacy of the legless mythology survives to this day, thanks to the rules of species classification. When Carl Linnaeus first described the greater bird of paradise in 1758 for inclusion in his ‘System Naturae’, he gave it the official name Paradisaea apoda, which translates as ‘legless bird of paradise’.

Apparently, it was Alfred Russel Wallace (the co-discoverer of evolution by natural selection), on his expedition to the Malay Archipelago in 1854-1862, who was the first European to see live birds of paradise.

He called them “the most beautiful of all the beautiful living forms that adorn the Earth”.

He also wrote: “The flesh is only to be eaten in necessity. It is dry and tasteless.”