Interview with a death historian

Louvain Rees explains what her job is all about and shares some of her favourite discoveries.

Last month while scrolling through Twitter I came across the following post:

Turns out that I’m not like most people, because my first reaction would be to say: ‘ooh, tell me more’.

So, I did just that and got in touch with Louvain to find out what her job is all about.

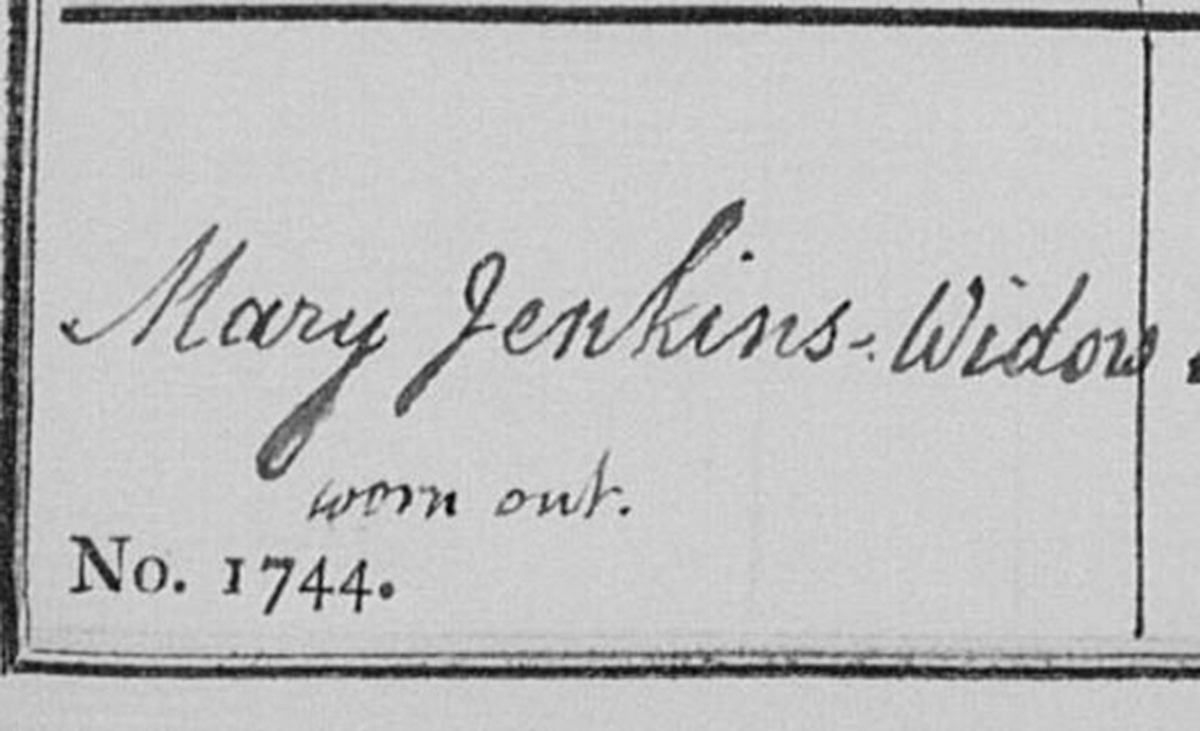

“I often tell people that I write about dead people for a living. For the most part, I spend the day going through census records, burial records, and archive material.

“The aim of my work is to explore Welsh mourning traditions, practices, and commemoration. More specifically, how they relate to the working-class and the poor,” she says.

“I like to write about people. I like to be able to look at a gravestone, a photograph, or a historical document and have some sort of concept of who that person was, what they did, and what their life was like.”

Louvain has been interested in history for as long as she can remember (her junior school had to buy ‘Horrible Histories’ books for its library because she refused to read regular story books!). Visits to historic churches piqued her interest in the lives of the people buried there. But it was a personal bereavement which definitively set her on her career path.

“I became more and more interested in social history as time went on, but it was always something I did as a hobby.

“My father’s sudden death in 2015 influenced my work tremendously. It made me face my own mortality. I wanted to know the process that his body would be going through during the transition from hospital bed to cremation furnace.

“This is when I became more interested in how we mourn and remember our dead. His death pushed me to take my interest in death history more seriously, and if I am honest, I probably wouldn’t be in the field I am if he hadn’t died.”

“My job enables me to explore some wonderful places – one of my favourites being the death collections at the National Museum of Wales. They are home to all sorts of things that a ‘normal’ person would describe as weird,” she says – from bracelets, brooches, and rings made of human hair, to mourning photographs, clothing, and samplers.

“Death and mourning now is seen as something to be kept private, whereas prior to the First World War, people were expected to be seen publicly mourning.

“Society today is quite closed off when it comes to talking about something that is inevitable. One of the reasons is that people fear death, which isn’t something new.”

What is different, is that – thanks to scientific advances and better and cheaper/free health care – “we are not exposed to death like our ancestors were”.

That was until coronavirus.

“The pandemic brought death into everyday life like it never had been before and has opened up a conversation about death.”

And that, Louvain says, can only be a good thing.

“I think people’s natural reaction to questions about death is to brush it off. People do not like to talk about things they are afraid of.”

But, she says, we should “talk about death as a part of life. Normalise asking questions about it”.

Fancy dabbling in a bit of death historianism yourself?

Louvain says: “I would definitely recommend it! There is nothing worse, in my opinion, than gatekeeping history. I strongly believe in making history – especially local history – accessible to everyone.”

She recommends:

FindAGrave as an excellent online resource to explore your local cemetery virtually: “I have the app on my phone and use it to track who I am looking for and check if people have already added information about them.”

Asking questions: “When you explore a churchyard, try and go into the church as there can be a lot of information about those buried there. And have a chat with the congregation – in my experience, they usually know things that a lot of other people will not know.”

Joining a local history society: “It can be a great way to engage with like-minded people.”

Sturdy shoes: “Most churchyards are uneven and sometimes there are holes in the ground.”