Issue 10: the secret history of occult arts in 19th Century Australia

Folk magic and superstition were alive and well among Australia’s English colonisers.

Dr Ian Evans has spent his career exploring the history and conservation of old Australian houses. But a trip to England in 2002 would set him on a curious new course.

It was at a house in Suffolk that Dr Evans was first shown evidence of “various things hidden within buildings” which were believed to imbue protection.

He thought: “if this practice was happening in England – people were hiding things in buildings, for magic purposes – there was every chance that they would have brought these beliefs with them when they came to settle in Australia.”

He suddenly realised that within the houses he’d been examining his whole career, “there was a big secret hidden, which I had not glimpsed, and neither had anyone else”.

On his return to Australia, he put out a call for evidence via an email network of heritage advisors and “within two days I knew I was onto something”.

“There were a number of reports of boots and shoes that'd been found. They weren't found in a cupboard or anything like that, they were underneath the floor, in chimney cavities, and in roof cavities. And there was just one shoe or boot in each concealment, so it was very strange.”

Over the following 20 years, through his Australian Magic Research Project, Dr Evans has discovered evidence of five distinct types of protective folk magic practiced in Australia in the 19th Century:

Concealments: items hidden in a building’s wall/roof/chimney cavities or under its floor – from shoes and clothing, to domestic artifacts, and even dead cats. The concealments were thought to act as decoys to lure evil spirits into voids from which they couldn’t escape.

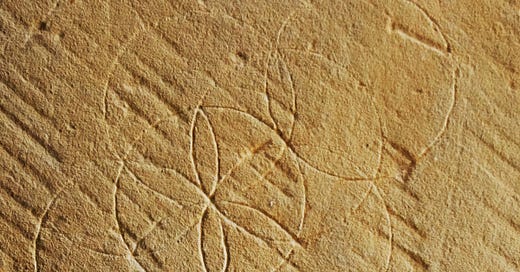

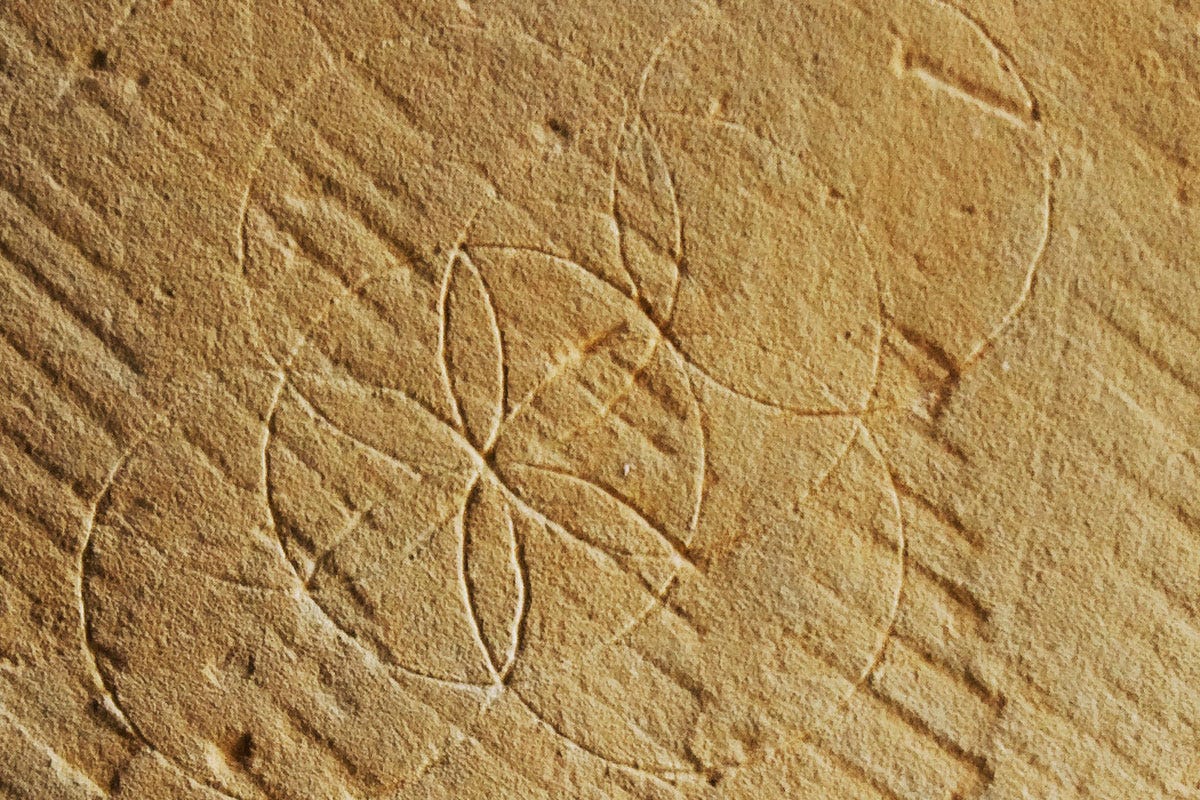

Hexafoils and concentric circles: carved using a compass or protractor and found at points of entry, such as chimneys (and sometimes on items of furniture). The carvings were thought to deter evil spiritual beings from entering, perhaps by trapping them within the complex structure of the design.

Candle or taper burn marks: deep scorches, deliberately made through repeatedly burning, scraping out the char, and burning again. Found in outbuildings such as stables and used to inoculate the buildings against fire (literally: fighting fire with fire).

X marks: incised by blacksmiths on iron strap door hinges, to protect buildings where animals or foodstuffs were housed.

Candle smoke marks: star/asterisk shapes comprising a series of individual carbon stains, made over the top of designs traced out in pencil. These marks are incredibly rare. There’s only one recorded instance in Australia (on the basement ceiling of a 19th Century former mechanics institute in Victoria), and only 16 sites found in England, all dating from the second half of the 17th Century. The marks were supposed to avert evil influences or bad luck.

Although based on considerable evidence gathered by researchers in the UK, Australia, and the USA over many years, Dr Evans says the explanations of the purpose of these marks can only be logical assumptions.

“The great problem we have is that they left no written evidence. There's nothing in the contemporary documentary archive about this.”

What this means, Dr Evans says, is that this knowledge of protective folk magic “all had to be word of mouth”.

“You must imagine how really remarkable that is in the 19th Century. They didn’t have the internet, they're not writing about it in magazines or books. They had to just whisper to each other that this is what you should do.”

Dr Evans has, however, found evidence in the archives for at least three “cunning” folk – or practitioners of magic – operating in Australia in the 19th Century (“and we'll gradually identify more of them as time goes by”).

In Tasmania, were William Allison, who travelled to Australia to work on a large property, and Benjamin Nokes, who was transported for life for burglary. Both went on to become publicans in the first half of the 1800s. Both were also known for their herbal treatments.

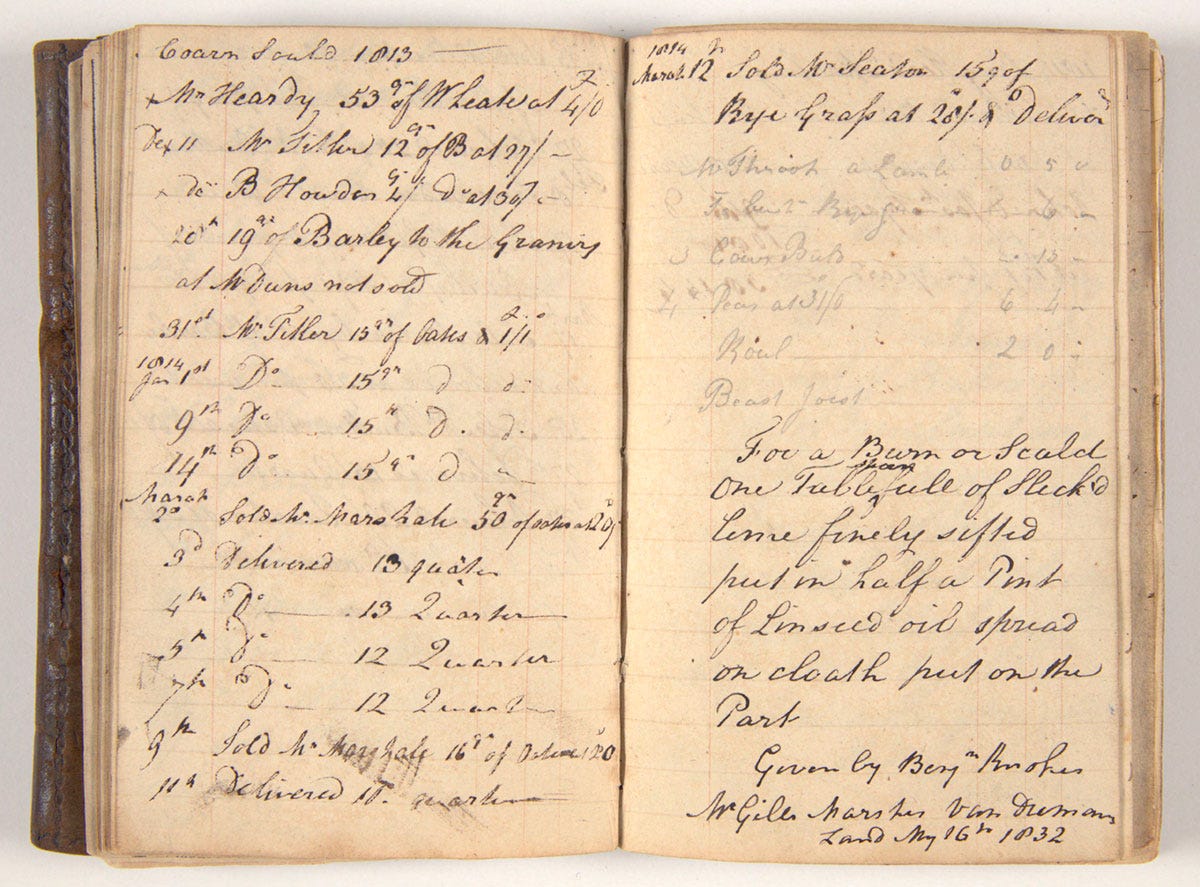

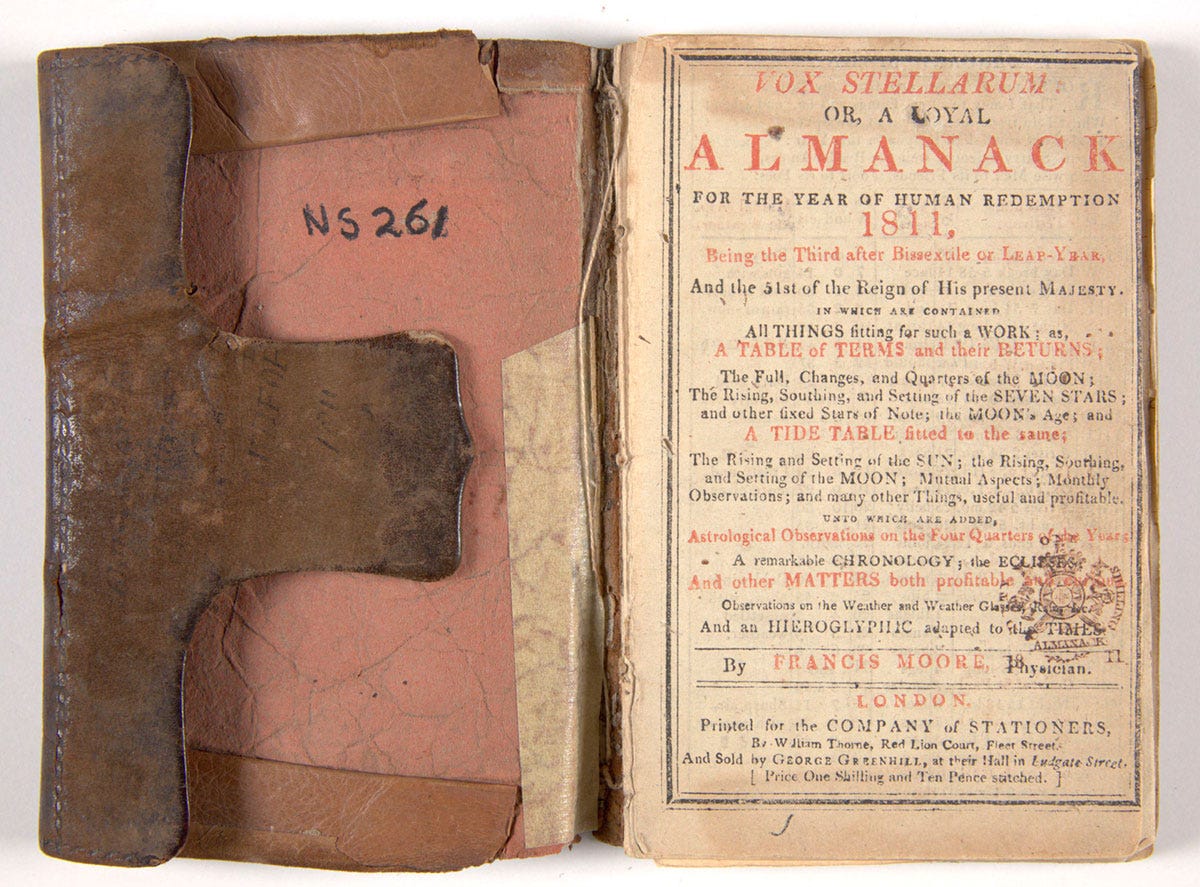

Incredibly, a tool of Allison’s trade survives. In the State Library of Tasmania is housed a “wonderful notebook”, an almanac from 1811, which “contains numerous recipes which were said to be useful for a variety of conditions”.

The almanac had been in the country's library collections since 1970 but was considered unremarkable – it was Dr Evan's research that revealed its significance. It is the only known first-hand, written evidence of the practice of folk magic in colonial Australia.

The book includes remedies for everything from headaches, burns, and colds, to rheumatism and its associated pains, ‘the gravil’ (kidney stones), and piles.

And there’s compelling evidence to suggest Allison and Nokes knew each other. One of the recipes in Allison’s almanac (‘For a Burn or Scald’) is attributed as ‘Given by Benjm Knokes at McGill Marshes, Van Diemen’s Land, May 16th 1832’; several others are credited to ‘BN’.

Nokes, who died in 1843, was listed as a doctor on his death certificate, but Dr Evans says “there’s no record of any such qualification”. Nokes was, however, well known and respected for his healing during his lifetime.

An article appeared in The Colonist and Van Diemen's Land Commercial and Agricultural Advertiser on 18 March 1834, celebrating Nokes’ success in curing “most obstinate cases of the gravel” (kidney stones).

(Allison’s recipe ‘For the Gravil’ appears to have three lines which carry onto a second page, under which appear the initials ‘BN’.)

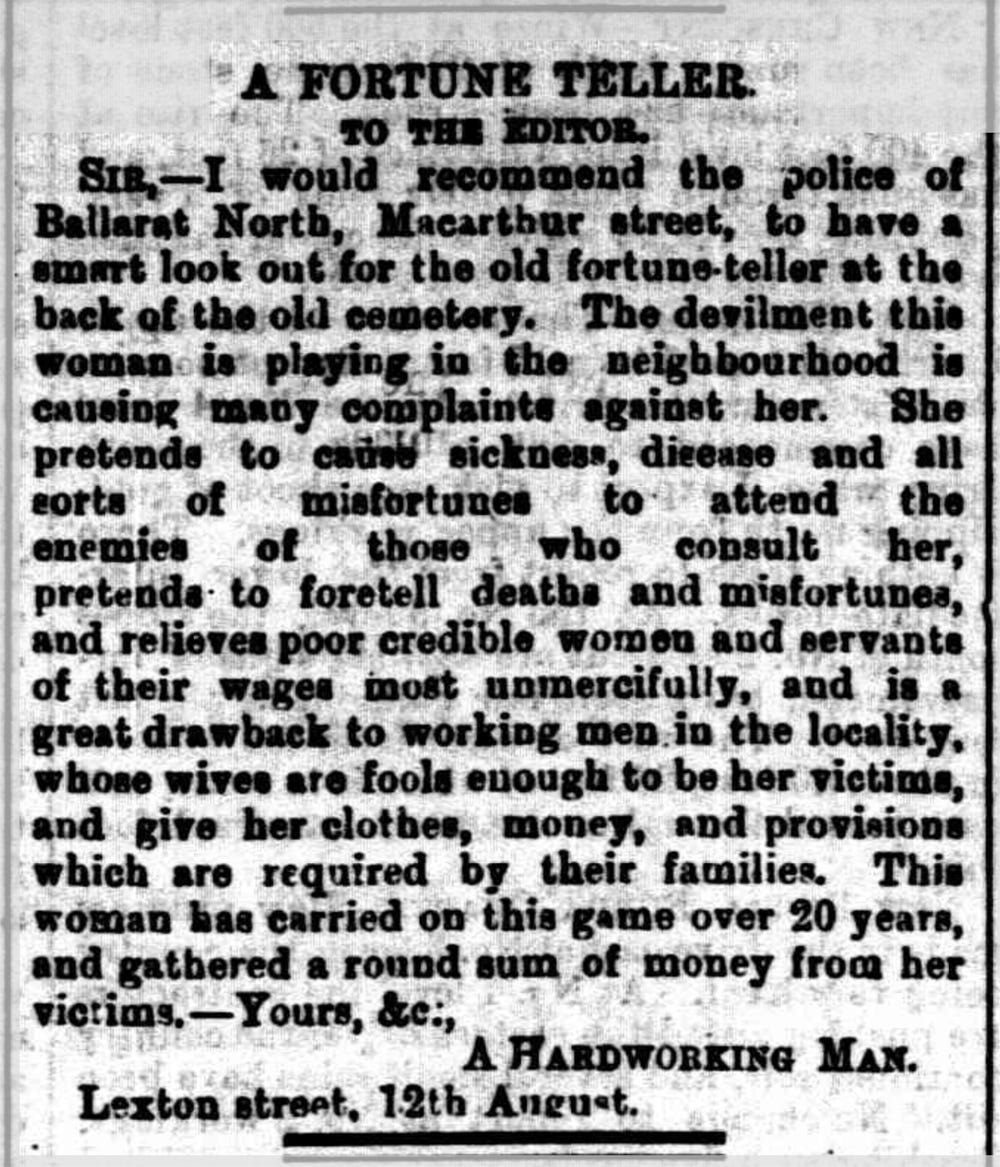

In Victoria, Mary Barrell operated as a fortune teller in the second half of the 1800s. In a letter to the editor of The Ballarat Star on 14 August 1882, a ‘Hardworking Man’ accused her of ‘devilment’ and ‘pretend[ing] to cure sickness, disease and… foretell[ing] death and misfortune’.

Dr Evans – who no longer actively conducts field work, but still “keeps a finger in the pie” – is proud that his work has uncovered this lost, secret history of the occult arts in Australia.

“People in the 19th Century were not dull. Superstition was alive and well.

“It's quite obvious that they believed in God – they built churches and they went to church. But there was something else going on in the background.

“There are examples of concealed boots and shoes in church buildings. I know of people seriously involved in the Catholic Church in Sydney who practiced (magic) in their home. I don't think they saw any conflict between religion and magic.

“They saw (evil) occurring with the various illnesses and accidents that people sustained, in the high death rate among children. So, they would pray to God for protection, and when that didn't seem to work, they resorted to the practice of magic. They took the power into their own hands to try to protect their families and make a difference in their lives.”