The isolated medieval church of West Thurrock

‘An oasis of the past in a modern industrial setting’.

Just over the border of far east London there is a church that’s been encroached upon by time and industry.

St Clement’s, West Thurrock, once stood on a strip of gravel on the banks of the Thames. It was part of the pilgrim’s route to Canterbury and Rome, a stop off before crossing the river. It is named for the patron saint of mariners and would likely have been used by local fisherman to pray for a good catch and a safe return.

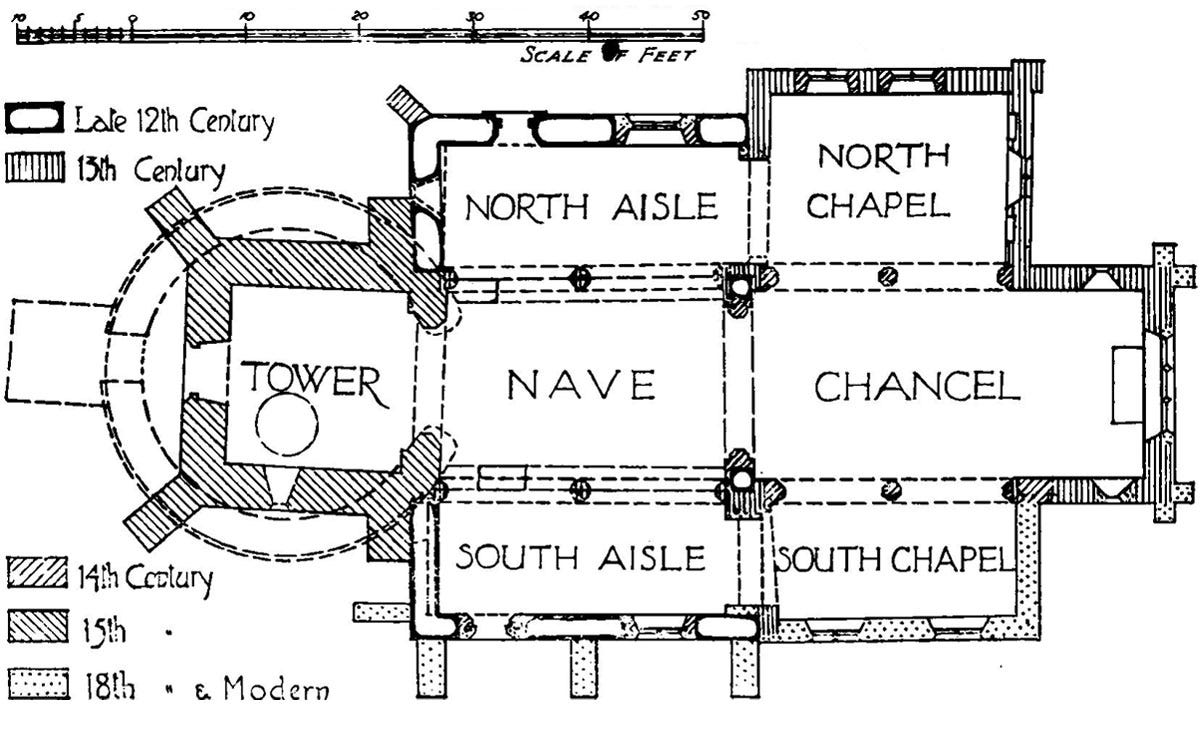

The Grade I listed church (the highest designation of protection for historic buildings) was built in the early 12th Century. It probably began life as a low, thatched building, before a round nave was added, modelled on the Holy Sepulchre at Jerusalem. There are only around 16 churches in Britain known to have had a round nave – a feature which is linked with the Knights Templars and Knights Hospitallers. (And indeed, historians have found evidence of the orders’ activity in the surrounding areas at this time.)

Across the centuries, the church has been widened (13th Century), its unique nave replaced with a large tower (15th Century), and external supporting buttresses added (18th Century). The marshes and land that used to surround it have been almost entirely built over.

By the 19th Century, observers were commenting on its isolation and increasing dilapidation. A report from 1866 described it as having ‘not a dwelling place near it, save the habitations of the dead’, and in 1871 it was said to be in a ‘state of ruin’. However, services continued, one and off, until the 1970s, when it was finally deconsecrated in 1977.

In 1940, a soap factory had begun operating next to St Clement’s. In his book on the history of the church, local historian Christopher Harold notes jokes about ‘cleanliness being next to godliness’. But in all seriousness, the factory became the church’s saviour. On the 50th anniversary of the factory’s opening, owners Proctor & Gamble took on responsibility for St Clement’s – restoring it and returning it to ecclesiastical and community use in 1990.

Regular services no longer take place, but it is open to the public one weekend a month from mid-spring to early-autumn, and available for hire. (You may recognise it from the funeral scene in ‘Four Weddings and a Funeral’.)

Today, an enlarged riverbank and sea wall protect St Clement’s from the Thames, and it stands, lonely, on a small patch of land – as Harold describes – ‘an oasis of the past in a modern industrial setting’.